Thai demand for higher education cooling as population ages

Thailand has been an attractive international education market for some time and continues to send substantial numbers of students for studies abroad, primarily to Australia, the US, and the UK. Numbers have declined for some destinations, notably the US, but others, such as Australia and New Zealand, have seen steady gains over the past five years.

Even so, it seems clear that overall growth rates in terms of outbound mobility are modest. UNESCO data indicates that the total number of outbound tertiary students has largely hovered around 25,000 per year for much of the past decade. For some destinations, Australia again being a notable example, Thai enrolment in English Language Teaching (ELT) programmes adds a significant increment to this tertiary base. But education and demographic trends in Thailand suggest that overall growth rates in outbound mobility will remain modest for the foreseeable future.

Thailand is often associated with its ASEAN neighbours for its notable economic growth and burgeoning middle class. There are, however, a couple of important distinctions when it comes to demand for education.

First, the Thai higher education system has expanded considerably through the 1990s and beyond, and there are some important indicators that supply now exceeds domestic demand, particularly in some programme areas.

There are 170 universities in Thailand today, which together offer around 4,100 academic programmes. In a rather stark indication of the emerging supply-demand gap, however, just over 105,000 Thai students sat university entrance exams in 2015 – in a system that can admit more than 156,000 new students per year.

That tens of thousands of university seats will go unused as a result is not lost on institutional leaders who are now considering their options, including gradually shrinking, or even closing outright, undersubscribed programmes. “The numbers are a wake-up call for university administrators to start thinking of changes in the number of students in each department,” says a recent item in the Bangkok Post. The macro numbers bear this out as well in that, after a period of significant expansion over the previous two or three decades, total tertiary enrolment in Thailand peaked in 2007 and has been essentially flat since (with modest year-over-year declines for most of the last decade).

Demographic trends are playing an important role here, and in this respect Thailand also sets itself apart from its regional neighbours. In most Southeast Asian countries, growing working age populations are helping to drive GDP growth and improved productivity. Not so in Thailand where the National Economic and Social Development Board projects that school-aged Thais (those 21 years and younger) will fall to 20% of the population by 2040, a dramatic decline from the roughly 62% of the population that they represented in 1980.

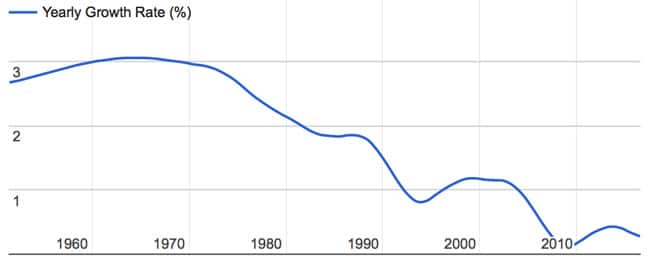

The issue has been, and is, the country’s low birth rate. Owing in part to earlier national policies that sought to reduce fertility rates, the population growth rate in Thailand has fallen from from around 3% in the 1960s and 1970s to .3% today.