A regional perspective on student recruitment in MENA

The countries of the Middle East and North Africa region, or MENA, have fast-growing youth populations that continue to drive growing demand for higher education. The region has quadrupled the average level of schooling since 1960, halved illiteracy since 1980, and today is one of the world’s most important sending markets for international students.

Given their proximity to each other, and often complementary market conditions, many international educators choose to adopt a regional orientation by targeting multiple MENA markets in their recruitment efforts.

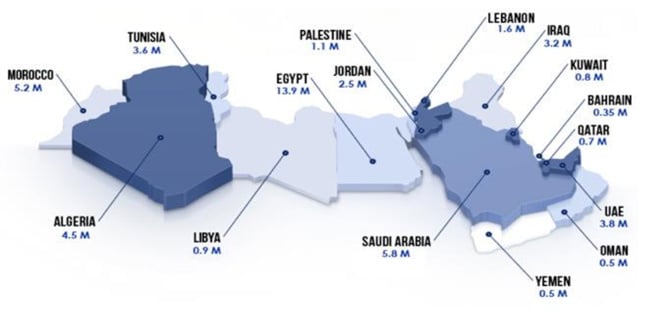

The current population of the region is about 523 million people, with 70% under the age of 30. According to the Population Reference Bureau, the number of MENA inhabitants will reach 700 million by 2050, which at current growth rates will make it more populous than Europe by that point.

Coupled with continued economic growth, these demographic trends have fuelled a boost in higher education enrolment rates over the past decade, with some estimates projecting a further 50% increase over the next ten years. Governments in the region have actively encouraged outbound mobility due to the limited capacity of local systems to absorb this growing demand. As a result, it is now more and more common for MENA students to study abroad.

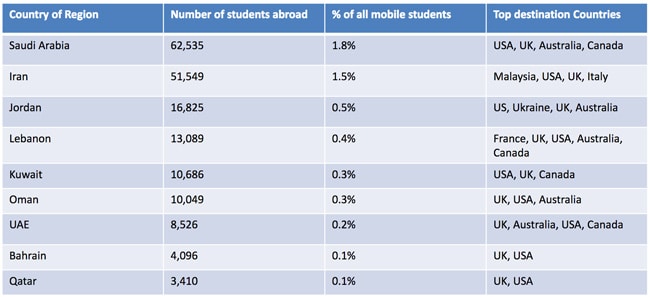

The top senders in the region are Saudi Arabia and Iran, with the former ranking fifth in global outbound mobility, and the latter tenth, according to UNESCO data from 2014. Iran recently had international sanctions eased, and the government has made decisive moves to bolster links with foreign educational institutions.

The following chart below summarises outbound mobility for a number of selected countries in the region.

Recruiting challenges

Government leaders understand that the rising tide of young people aiming for university admission could become an engine of growth for the region. But even though public expenditure on higher education in the region is significant, it has not kept pace with demand over the past decade and many institutions and schools are struggling with capacity issues. Education First’s (EF) most recent assessment of English proficiency in the Middle East and North Africa notes: "Many of the countries in the region spend more per pupil than countries in Asia with similar levels of development, but this higher investment is not delivering better results." The report reveals as well that Jordan, Tunisia, Qatar, and the UAE are all well below OECD averages not only in English, but also in math and science. Many observers have raised quality concerns with respect to graduate outcomes in the region. Employers report that only about one third of new graduates are ready for the workplace. And interestingly, students believe the same. Only a third of students in a recent survey considered they were adequately prepared for employment. But more than a third also expressed a willingness to pay for further education to increase their job prospects. Their anxiety about securing jobs is backed up by data. Youth unemployment is high at 21% across the Middle East and 25% in North Africa. When measured against other geographical regions, MENA has the highest youth unemployment in the world, and about 30% of the unemployed hold university degrees. International educators should also be aware that public support for study abroad can be low in some markets in the region. Egypt, for example, offers only a handful of grants despite a burgeoning higher education enrolment that shot up by a half million students between 2000 and 2015. One notable exception to this is Saudi Arabia, where the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques Scholarship Programme (previously the King Abdullah Scholarship Programme, or KASP) has aided hundreds of thousands of students since its inception in 2005 and, even with recent signs of budget restraint, is still slated to run until at least 2020. Qatar, Kuwait, and the UAE also offer scholarship support for students going abroad, albeit on a much smaller scale than has been the case in Saudi Arabia for some years now. Patience is a must when working in the MENA region. The regulatory landscape is fragmented, and clarity can be lacking. Document preparation, granting of licenses, and government functions can all take longer than would be expected in the West. Countries such as Iraq, Algeria, and Iran rank highly in ease-of-business metrics, whereas Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar rank near the bottom, according to a 2013 study conducted by the World Bank. The level of conflict and instability in the region is naturally also a concern. In addition to an economic slowdown spawned by lower oil prices, military action and civil war have severely damaged the economies and infrastructure of Libya, Yemen, Iraq, and Syria. The total number of people displaced from these countries may be as high as 15 million.

Making contact

MENA students are highly active and engaged online and this means that social platforms and other online services are an effective channel for reaching prospects in the region. Facebook, with an 89% penetration rate across the region, is the top choice of young people when measured in aggregate. Egypt alone boasts nearly 14 million Facebook profiles, compared to Saudi Arabia’s six million and Morocco’s just-over-five million.

Springing forward

One effect of the 2011 citizen uprisings known as the Arab Spring is that public expenditure on education received a boost in MENA. Some governments realised the need to invest in education not only to ensure growth, but also to maintain social stability. Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have been at the forefront of increases on educational infrastructure, and other MENA countries are following suit, although, as noted above, many are nevertheless struggling to keep pace with the growing demand for higher education across the region. As the past several years have amply demonstrated, many students and families continue to look abroad for education. Study abroad has become an important aspect of the culture of education in many MENA markets, one that can be expected to persist through the ups and downs of scholarship funding and other local market conditions.

Most Recent

-

As Iran retaliates across the Middle East, schools close, students worry, and institutions reassess transnational education Read More

-

US: Student visa issuances fell by -36% in summer 2025; OPT uncertainty among factors affecting international student demand Read More

-

Canada and India deepen educational ties; India repositions as an equal player in international education Read More