Ghana emerging as an important sending market in Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa has become an increasingly important region for international student recruitment, and is home to a number of significant emerging markets, notably Nigeria and Kenya. The region sent just over 33,500 students to the US in 2014/15, and a similar number to the UK.

But the potential is there for further growth, driven in part by large youth populations, rising incomes, and by a demand for higher education that cannot be fully met at home.

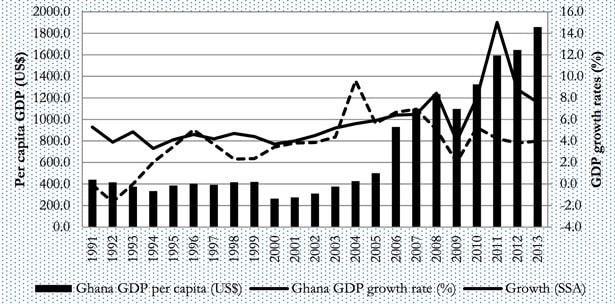

This is certainly true of the West African nation of Ghana, a country that has been one of Africa’s strongest performers in terms of economic growth and which has outpaced overall growth rates in Sub-Saharan Africa over the past decade and more.

Tumbling oil prices triggered a slowdown in 2015 and 2016, but economists anticipate that the economy will return to form and perform closer to long-term averages of 6-7% growth per annum from 2017 on.

Employability and skills gaps

This point is borne out by employment levels in Ghana, which remain only marginally higher than regional averages. The national unemployment rate has hovered around 5-6% in recent years, but is notably higher among Ghanaian youth (10-12% between 2010 and 2013). A closer look at employment trends suggests as well that many of the jobs in Ghana are in the informal sector, and can be classed as vulnerable to some extent. Ironically, unemployment rates are higher among those with secondary school or tertiary education, reflecting in part the limited job opportunities available in the public or corporate sectors for those with more advanced education. "The relatively higher unemployment rate among the educated is an indication of limited job creation in the formal sector to absorb the increasing number of tertiary and secondary school leavers," adds Brookings. There is a chicken-and-egg aspect to this unemployment pattern as well in that the Ghanaian economy is clearly shifting away from agriculture and toward resource and service industries. However, only a small percentage of the country’s labour force has completed tertiary education and recent studies have pointed to significant skills shortages and skills gaps across the economy, particularly in the professions and in a number of technical and vocational areas. This points to an underlying issue in Ghanaian higher education and the employability of its graduates in particular. "Ghana tends to produce a large number of humanities graduates, in excess of what the economy requires, while the scientists, engineers, and technologists needed for the manufacturing sector are produced in limited numbers," says Brookings. "Even though enrolment in science subjects in public universities and polytechnics has been inching upwards in recent times, the improvement is very slow." A recent British Council study adds that there is also widespread concern among employers in the region as to suitability of local graduates. "While employers are generally satisfied with the disciplinary knowledge of students, they perceive significant gaps in their IT skills, personal qualities (e.g. reliability) and transferable skills (e.g. team working and problem solving)." Writing in The Guardian earlier this year, Phillip Clay, a former chancellor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, underscores the broad issues at stake for Ghana and for the region as whole. "There are fewer than 2,000 colleges and universities on a continent with a billion people in 55 countries. In comparison, the US is home to more than 4000 institutions for 320 million people. Less than 7% of Africans have college degrees compared to 30% of North Americans and Europeans. More than half of Africa’s population is under the age of 30. This is either a demographic dividend, if the talent is developed, or a demographic curse if the next generation is large, economically marginal and unable to do the work of advanced economies."

Quality an issue as well

In pursuit of this demographic dividend, demand for higher education in Ghana continues to expand in line with the country’s growing economy. But this is in turn putting a strain on the higher education system. "Expansion in the context of limited public funding has placed the system under significant strain," says the British Council. "In many cases, lecturers lack adequate qualifications and preparation themselves, and transmission-based pedagogy and rote learning are commonplace. Universities have also suffered a severe lack of physical resources, including buildings, laboratories and libraries." As in many other emerging markets, Ghana’s government has attempted to ease the pressure with help from the private sector. A number of new private universities, most of which are affiliated with accredited public institutions, have opened their doors in the last decade. According to the country’s National Accreditation Board, there were 69 registered private tertiary institutions in Ghana as of the end of 2015. As Professor Clay’s earlier point highlights, however, higher education remains an option for a relatively small percentage of the Ghanaian population, and total tertiary enrolment in the country was just under 300,000 in 2015, of which roughly 22% (64,112) were enrolled with private institutions. Significant quality questions have been raised about private universities in Ghana as well, an issue which the institutions themselves have recently moved to address through the formation of a shared quality assurance unit that will "appraise programmes and degrees to meet local and international standards."

Push factors for mobility

All of these factors - a growing economy, a large youth population, significant skills gaps, and quality issues in higher education - are also combining to fuel greater demand for study abroad among Ghanaian students and their families. The number of Ghanaian students abroad continues to grow, and was estimated by UNESCO at just under 9,000 in 2013. More detailed or updated figures are scarce but given the incomplete mobility data available for many Sub-Saharan markets the UNESCO estimate likely understates actual student movement from Ghana. In any case, Ghana has clearly become a more important sending market in the region in recent years. It is now the second-largest source of Sub-Saharan students in the US, after only Nigeria and after having edged out Kenya for the number two spot as of the 2014/15 academic year. More than half of all outbound students choose the US or UK, with the balance distributed among institutions in Canada or in Europe. For all of these reasons, Ghana is likely to assume a larger role in the international education landscape going forward, both for recruiters aiming to expand their enrolment from the region and also for institutions that hope to help build a stronger domestic system through partnerships and the provision of programmes in-country.