Chile continues to push for improved English proficiency

, largely driven by the need for English-speaking professionals, academics, and technicians to staff its increasingly internationalised industries. Chile has a large economy fuelled by mineral production, particularly copper. However, the government sees economic diversification as the path to a more prosperous and stable future, and education policy as a key component of achieving this goal. Part of this policy is a move toward a fuller integration with the global economy, and toward bilingualism, with English as the primary second language to be adopted.

In 2003, the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) launched Programa Inglés Abre Puertas, or the English Opens Doors Programme. This initiative was specifically enacted with economic development in mind, and its goal was to give all young people at least some proficiency in English. It was aimed at all students, but centred on those who were disadvantaged. The government thought this would boost the country's global competitiveness, reduce inequality, and democratise opportunities for young Chileans.

However, by 2010, TOEIC Bridge test results indicated that only 11% of grade 11 students had reached A2 or basic level in English. While this was an improvement on the 5% result from 2004, the government had hoped A2 level would be reached by grade 8 students, and that grade 12 students would reach B1 or independent level by 2013. In addition, outcomes differ radically between rich and poor communities, mainly due to the fact that private school students begin learning English earlier and benefit from more teaching hours.

Data from EF Education First charts Chile’s efforts to raise its proficiency. In 2011 the country ranked 36 of 44 surveyed, with "very low" proficiency. 2012 and 2013 saw increases that pulled Chile’s ranking up to 38 of 52, then 44 of 60. But in 2014 Chile landed in 41st place out of 63 ranked nations, and 2015 brought a ranking of 36 out of 70. These results are relative to other countries but Chile’s overall proficiency has increased in five years from "very low" to "low," moving it past nations such as China, however on the whole other countries in the survey are also improving.

English and the people

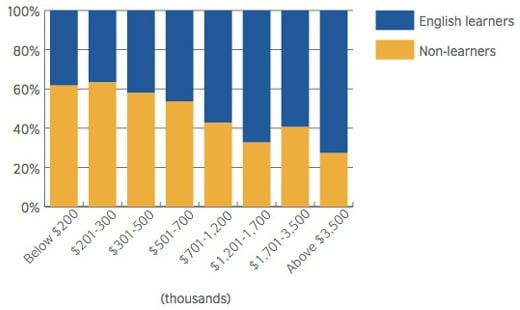

Despite the logistical problems EODP has faced, an awareness of the benefits of English in the globalised economy has spread among the general population. A widely publicised study by the British job recruitment and employment agency Adecco showed that English speakers earned about 30% more than non-English speakers, and further survey data compiled by the British Council gives a clear picture of how English proficiency correlates to income in Chile.

Government policy

Chile’s geography has presented special challenges to government plans to increase English proficiency. Extending 4,300 kilometres north to south, much of the country is remote and mountainous, which presents obstacles to implementing policies evenly nationwide. Transport can be problematic. In smaller schools students are often taught in classes with no regard for age or grade, and in some areas school attendance is low. All of these characteristics present problems to administering quality English training. Despite some problems in Chile’s ELT sector, demographic and market forces point toward overall demand for English increasing in coming years. However, Chile is one of the most economically unequal countries in Latin America, which means the best opportunity for international educators to attract a full spectrum of students lies with scholarship programmes such as Pingüinos sin Fronteras (Penguins Without Borders), a programme for secondary school students established in 2013, Semillero Rural, which focuses on vocational and technical training (especially in the agriculture sector), and BECAS Chile. Families may have an uptick in available funds for education if President Michelle Bachelet follows through on her promise to ensure free education for all. She had initially announced a March 2016 timeline for achieving this goal, but at the moment only 14% of students in the poorest households attend university tuition-free, according to a study by Confech. Just weeks ago 120,000 students marched to demand progress on the free education front, as well as protest school privatisations and high student debt. The government’s programme, however, hit another roadblock when Chile’s Constitutional Court blocked part of the free university proposal, necessitating changes to the plan. President Bachelet now promises that 70% of students will be receiving free higher education by 2018, and that universal access will be achieved in 2020. Education costs are no small matter in Chile. For those who find themselves outside the free-tuition scheme Chile remains one of the most expensive countries in the world in which to obtain a standard bachelor’s degree, when cost is measured as a percentage of household income. This means parents often take on crippling debt in order to pay for higher education-and is one reason the free-tuition movement has enjoyed up to 81% support for the general public. Chile’s education reforms, while not directly focused on English proficiency, will ultimately change how language teaching is administered. Some of the new policies will place pressure on private schools, which could affect cost at these institutions in a way beneficial to the general population. The EODP means that English will be taught sooner and in more communities, while nationwide free university tuition, if it comes to pass, will boost learning opportunities for college students. All that to say, the expansion of English Language Teaching and English proficiency in Chile is destined to accelerate. For additional background on this important Latin American market, please see our recent post, "Targeting demand for study abroad in Chile."