Further evidence of the mounting costs of UK visa policy

It has been clear for some time that more restrictive visa policies are weakening foreign student enrolments in the UK. And now both the UK’s Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) and Universities Scotland have published new research showing how much damage the policies are inflicting in terms of lost opportunity and income for the university sector as well as the economy as a whole.

Business enrolments down

The UK’s Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) has released a report, UK Business Schools and International Recruitment: trends, challenges, and the case for change, showing that international student enrolments in university business courses are falling dramatically: down 8.6% in 2014/15 compared to the previous year. This is particularly alarming given the prominent demand for business studies among international students. According to CABS, a third of all foreign students in British universities are enrolled in a business administration programme.

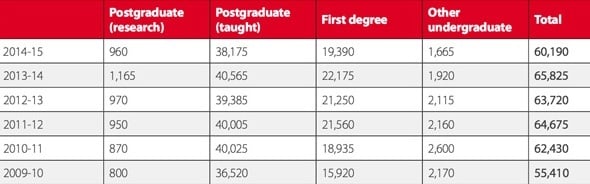

The value of international students studying business courses in the UK is massive: CABS estimates that these students contribute £2.4 billion (US$3.4 billion) to universities and the UK economy. However, these expenditures can only be on the decline given that the number of non-EU students in British business schools fell from 65,825 in 2013/14 to 60,190 in 2014/15.

Findings from Scotland

Universities Scotland has also released research to bolster its argument that the 2012 abandonment of a post-study work visa obtained by Scotland in 2005 – which allowed non-EU graduates to stay and work in Scotland for two years – has had a dramatic negative impact on the economy. The peak body contends that scrapping the visa has drained the Scottish economy of more than £250 million (US$355 million) over the last three years, and that 5,400 international students who otherwise would have studied in Scottish institutions did not due to the policy change. Moreover, it estimates that a decline in students coming from two key sending countries alone, India and Nigeria, has resulted in a £145.7 million (US$207 million) revenue loss for Scotland. Universities Scotland told the Scottish Parliament's devolution (further powers) committee that its economic impact estimates are "conservative," adding, "Scotland will have undoubtedly experienced a bigger negative economic impact as a result of this policy change in 2012. There would have been additional indirect economic benefits as a result of a larger number of highly skilled international graduates contributing to the Scottish labour market through increased productivity, increased tax contributions, and disposable income once in employment." Regardless of party affiliation, Scottish members of parliament have been calling on the UK government to allow Scotland to develop a replacement scheme for the abandoned post-study work visa, which many credited for having given Scotland a competitive edge among destination countries when it was introduced in 2005. That visa was in fact taken up across the UK after 2005, but then scrapped across the board. Universities Scotland has stated the need for a change in immigration policy succinctly:

"Scotland is losing out in the recruitment of international students to Australia, New Zealand, America and Canada because the UK has one of the least competitive policies on post-study work in the English-speaking world.

- The UK’s current student immigration policy is to the detriment of Scotland’s universities and to Scotland’s economy as international students generate over £800 million of income every year. Around half of this economic impact is in off-campus expenditure.

- The UK’s current student immigration policy is to the detriment of Scotland’s business and industry as there are high-skill shortages across a number of sectors that are not being met by UK and EU-domiciled people.

There is support for a change in immigration policy among university Principals, staff and students, among business leaders in Scotland and across all political parties within the Scottish Parliament."

The political import of the question goes beyond its economic impact in Scotland. The restoration of post-study work rights in Scotland was explicitly addressed (and recommended) in a post-referendum process looking at further devolution of powers in 2014. But so far it seems the British government is not considering allowing Scotland any variance from UK-wide visa schemes. Scotland’s The Herald newspaper reported in February that immigration minister James Brokenshire "claimed that current UK-wide visa schemes for international students amounted to an ‘excellent’ offer." Secretary of State for Scotland David Mundell has also appeared to have recently ruled out a distinct post-study rights option for Scotland, and this in turn prompted Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon to speak out directly on the issue for the first time earlier this year. "We are deeply disappointed, and I have to say I’m rather angry, that the Secretary of State for Scotland recently indicated, without any real consultation, that there is no intention on the part of the UK Government of reintroducing the post-study work visa for Scotland," said the First Minister. "I believe there is a consensus in this parliament and out there in Scotland to reintroduce the post-study work visa – and I think it’s time the UK Government got on and did it."

No changes for now

Late last year, we reported on signs that the British government might be considering a move to exclude international students from its net migration reduction targets as a result of the sustained critique of current visa policy from educators and stakeholders. So when the British Treasury set a goal to increase non-EU enrolment by 55,000 additional students by 2020 and announced a provision allowing dependents of foreign post-graduate students would be entitled to work during their stay in the UK, there was a glimmer of hope that things might be turning around. This hope was bolstered when Jo Johnson, Minister for Universities and Science, announced the government’s commitment to increasing overall education exports from £18 billion in 2012 to £30 billion by 2020. But so far, the British government has not linked the achievement of such ambitious targets to a more welcoming visa and work environment for international students. Efforts such as those by CABS and Universities Scotland to make clear just how much is at stake – and how much has already been lost - are clearly aimed at moving this policy discussion forward in the UK.

Most Recent

-

US: Student visa issuances fell by -36% in summer 2025; OPT uncertainty among factors affecting international student demand Read More

-

Canada and India deepen educational ties; India repositions as an equal player in international education Read More

-

Inbound, outbound, and transnational: the landscape for international education in China continues to evolve Read More