Small US colleges feeling the squeeze from “soft” tuition revenues

It is hardly a new idea that there are some important pressures on the traditional business model for higher education in the US. The population of college-aged students in America is projected to remain essentially flat over the next decade, competition is increasing, and US students and families are increasingly sensitive to the costs of higher education. The US is not alone in this and similar conditions exist in a number of countries, particularly in the developed economies that receive the majority of internationally mobile students. But a recent report from Moody’s Investors Service sheds new light on the situation in American higher education and highlights an emerging structural challenge for smaller US institutions in particular. The report, "Small College Closures Poised to Increase," has triggered a number of news headlines and discussions over the past few months. For the most part, these have focused on the report’s lead findings:

- The number of small colleges that will close annually will triple by 2017. In this context, "small" means a private institution with annual revenues of under US$100 million, or a public institution with revenues below US$200 million. Over the last decade, an average of five four-year public or private not-for-profit colleges have closed in the US each year. The implication of the Moody’s forecast is that the number of closures will increase to 15 per year (or more) by 2017.

- Similarly, the report projects an increase in merger activity among smaller institutions. On average, there were two to three mergers per year involving small US colleges between 2004 and 2014. Moody’s expects this merger rate to "more than double" by 2017.

The main factor in this forecast is the intense revenue pressure facing smaller institutions in the US. The report is also careful to point out, however, that even with this significant rise in closures and mergers less than 1% of the 2,300 four-year colleges in the US will be affected. It adds as well that, "Even in the face of material financial challenges, small colleges have proven to be tenacious. In some cases, deep stress can serve to mobilise alumni and other donors to provide extraordinary gift support. The presence of tenured faculty, donor restricted endowments, and the intervention of state attorneys general also complicates the decision to close. The 2015 case of Sweet Briar College in Virginia underscores these themes as the decision to close was reversed, at least temporarily, amid increased donor support, legal challenges, and other advocacy for the college’s continuance. Small public universities are unlikely to be closed due to political support and their community roles, but may be merged with other institutions or into systems where they can benefit from greater economies of scale." Indeed, another 2015 report - this time from the higher education consulting group Academic Impressions - provides a detailed commentary on the strategies four small US institutions are using to buck the trend. The report largely describes a sample of small colleges that have embraced a culture of strategic innovation and experimentation as a response to these pressures on the traditional college revenue model.

The story behind the story

Behind the headlines arising from the Moody’s report are two underlying findings that are likely to have far-reaching effects on American higher education, and that certainly will extend well beyond the still-relatively small number of institutions impacted by the closures and mergers forecast for 2017.

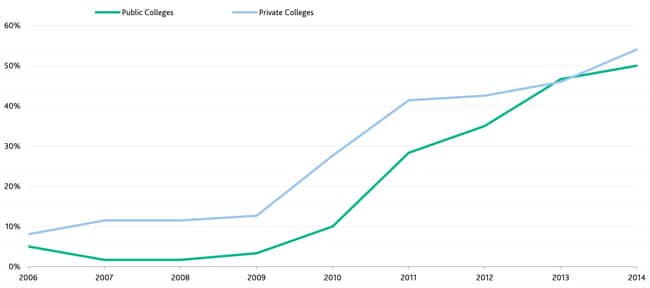

First, a majority of small US colleges are now no longer able to sustain revenue growth at a level that can keep pace with inflation. The benchmark that Moody’s uses to measure this is a sustained three-year growth rate of 2%. The significance of this is that if you can’t hit that 2% mark as an institution, then your costs are very likely growing faster than your revenues.

As the following chart illustrates, the percentage of small US colleges in this position rose from under 10% in 2006 to just over 50% as of 2014.

Put another way, the average private college in the study discounted its freshman tuition by nearly half in 2015.

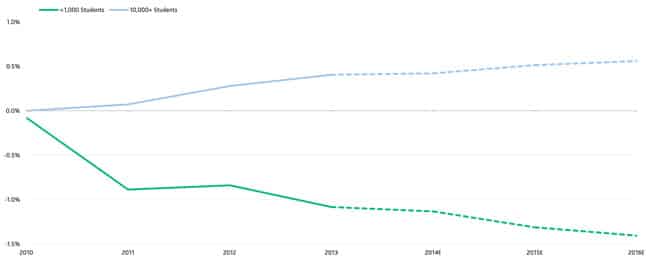

These conditions are made even more serious by a second underlying finding from Moody’s: smaller colleges in the US are losing market share to larger institutions. Another chart from the report, which follows below, shows that, from fall 2010 on, institutions with 1,000 students or less have been losing students to institutions with enrolments of 10,000 or more.