India’s employability challenge

India is home to 1.27 billion people and so many other dizzying statistics. More than half of the population is under the age of 25, and, with a projected average age of 29 years, India will be one of the world’s youngest countries by 2020. It also has the world’s second-largest population of higher education students, and is projected to surpass China in that respect in the next decade.

The quality challenge

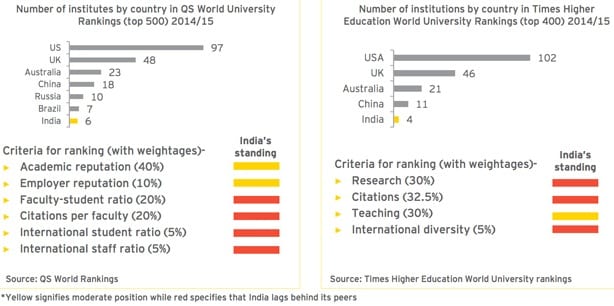

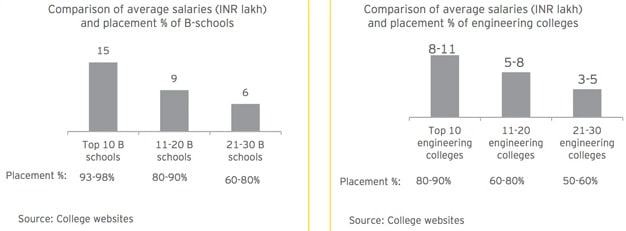

The obvious question that accompanies such a rapid expansion of higher education is whether or not quality can be maintained, and India is already facing some serious hurdles in this respect. In spite of the massive scale of its higher education system, for example, very few Indian institutions are globally ranked. As the following charts reflect, Indian higher education lags behind the systems of other key emerging markets on a number of important benchmarks.

- Outdated, rigid curricula and the absence of employer engagement in course content and skills development.

- Pedagogies and assessment are focused on input and rote learning; students have little opportunity to develop a wider range of transversal skills, including critical thinking, analytical reasoning, problem-solving and collaborative working.

- High student:teacher ratio, due to the lack of teaching staff and pressure to enrol more students.

- Separation of research and teaching; lack of early stage research experience.

- An ineffective quality assurance system."

The link to employment

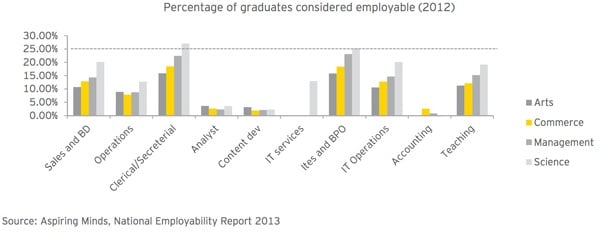

Global rankings are one thing but perhaps the most telling indicator of the quality of higher education in India currently is the employment outcomes of its graduates. As the following chart reflects, the vast majority of graduates - on the order of 75% or more - are not considered employable.

Most of the graduates from Indian higher education are not receiving an education that sufficiently prepares them for the demands and opportunities of the country’s rapidly changing economy.

The British Council points out, however, that "excellence" is a core priority for the current five-year planning cycle in Indian higher education, and plans for 2013-2017 emphasise the following:

- "improvements in teaching and learning, and a focus on learning outcomes;

- faculty development to improve teaching;

- increased integration between research and teaching;

- more international partnerships in teaching as well as research;

- better links between industry and research to stimulate innovation;

- connecting institutions through networks, alliances and consortia."

Even so, the scale of the challenge is daunting to say the least. Not only is the government striving to remedy widespread quality issues arising from the rapid expansion of the previous decade, it is also in the midst of a similar further expansion that will roll out over the next several years.

A vision for the future

A recent paper from the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) and EY sets out some bold targets for a more competitive and globally prominent Indian education system. Higher education in India: Moving towards global relevance and competitiveness calls for 20 Indian higher education institutions to be ranked among the world’s top 200 by 2030. It also advocates a target of 500,000 foreign students enrolled at Indian institutions by that same year (and 5% international faculty in the system). This is a fair cry from the 20,000-30,000 foreign students that have studied in India in a typical recent year, and illustrates the distance to travel between the current reality and any such 15-year target. The same is true of employability. The FICCI/EY study proposes that 90% of graduates be "readily employable" by 2030, and not just at home. The paper argues that India could be the world’s largest supplier of talent by "enabling higher education graduates with global skills, who can be employed by or serve workforce-deficient countries." These targets are potentially transformative in both their scale and ambition. They also notably include a significant international dimension, in terms of faculty, student mobility, movement of graduates, recognition and ranking, and international collaboration. This suggests nothing less than a nearly complete transformation of India’s current position in global education, from one of the world’s most important sending markets to a more complete player in international education. It also anticipates a higher education system that can truly address the profound economic and social change the country is undergoing today.