Bangladesh struggling to keep up with demand for higher education

The South Asian nation of Bangladesh is one of the world’s most densely populated countries. Currently the eighth-largest state by population, Bangladesh is home to more than 160 million people. It is bordered by India to the west, north, and east, and Burma to the southeast. Previously a province of Pakistan, Bangladesh is a relatively new country that secured its independence in 1971. Most Bangladeshis are Muslims and the official language is Bengali. The unofficial second language, however, is English, and it is widely used in higher education as the language of instruction at both private and public institutions. Just over half of the country’s GDP is generated by the service sector, but even so, nearly half of its people are employed in agriculture. Poverty remains a massive issue in Bangladesh, with nearly a third of the population (31.5%) at or below the national poverty line. However, the Bangladeshi economy has begun to transform itself over the past decade or more, and has clearly established a pattern of strong and steady growth over the period. "For the last 20 years the economy of Bangladesh has been growing at the rate of 5% on average," says Shamsul Haque, the vice-chancellor of Northern University Bangladesh. "This growth has been witnessed by the changing composition of GDP in the major sectors. Currently over 50% of GDP comes from the service sector and about 30% from manufacturing industries, and agriculture contributing to just under 20%. This transformation in the economy created demand for higher education in the country."

Burgeoning demand for higher education

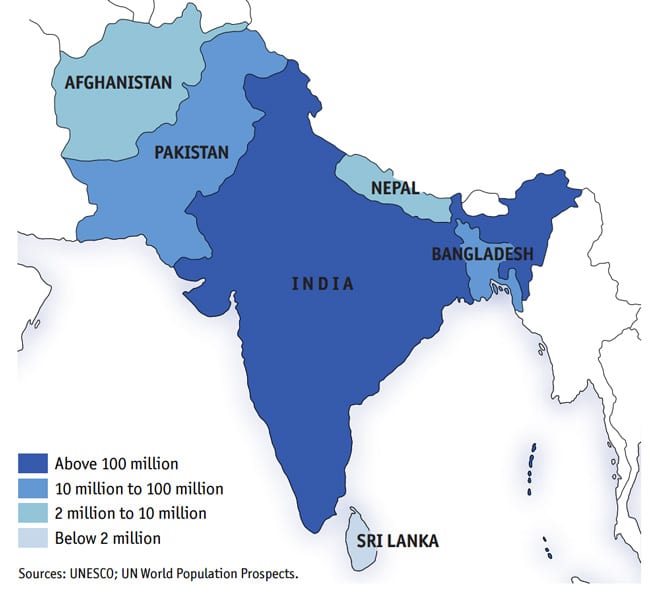

Bangladesh shares the same challenges of many of its South Asian neighbours: its economy is growing quickly as is its large, youthful population. 34% of Bangladeshis are aged 15 or younger, and the country has an opportunity to realise the full benefit of this “demographic dividend” in the years ahead - but only if it can provide education and training to the millions of students who need it.

"Rising demand in South Asia for higher education is currently not being met," reports the British Council. "As South Asian countries forge a path towards growth of their industry and services sectors, the role of the higher education sector in facilitating a skilled, knowledgeable workforce has become critical."

Indeed, Bangladesh has seen a tremendous increase in enrolment over the last decade or so. Total tertiary enrolment has nearly tripled since 2000 and surpassed two million students in 2012. But even with that growth, overall participation ratios are quite low, to the point that only 13.23% of college-age students were enrolled in higher education in 2012, as compared to 24.80% in India or 26.70% in China for that same year.

The overall enrolment growth since 2000, however, is an important indicator of a dramatic spike in demand for higher education. Looking ahead, the British Council counts Bangladesh – along with Nigeria, the Philippines, Turkey, and Ethiopia – among the emerging economies with the greatest forecast growth in tertiary enrolment for the next decade.

Domestic tertiary enrolment is forecast to increase by another 700,000 students through 2022, meaning that the total number enrolled in higher education will approach three million by that point.

Outbound keeping pace

Just as the increase in domestic tertiary enrolment reflects an underlying surge in demand over the last ten to 15 years, Bangladeshi outbound mobility has also grown over this period. Just over 7,900 Bangladeshis pursued higher education abroad in the year 2000, but that number had tripled by 2013. UNESCO tells us that an estimated 24,112 Bangladeshi students went abroad that year, with a fairly balanced distribution among major study destinations. Interestingly, most students pursue their studies outside of the region. The UK was the leading choice among Bangladeshi students in 2013 (4,204, or 17.44% of the total), followed by the US with 3,664 students (15.20%), Australia with 3,603 (14.94%), Malaysia with 2,003 (8.31%), and Canada with 1,530 students (6.35%). Add Japan and the 1,364 Bangladeshi students that it hosted in 2013, and those top six destinations together account for just over two-thirds of all outbound mobility from the country. Demand for an overseas education is being fueled by a supply-demand gap at home, but also by persistent quality issues in Bangladeshi higher education and by corresponding issues of employability. A recent British Council report makes the following general observation of education outcomes in the region: "An unfortunate by-product of the low quality of higher education – both for the economies of the region and the students themselves – is the low employability of graduates who emerge from the universities. Though there are notable exceptions, as a general rule, employers in South Asia are more inclined towards graduates from the large public universities."

Growing role of private providers

Study abroad is one solution to a capacity crunch at home. But an expansion of the system through growing participation of private-sector providers is another. With the country’s independence in the early 1970s, many schools and institutions in Bangladesh were brought under state control. The National University was established in 1992 and functions as an umbrella institution to administer exams and award credentials for a large network of affiliated colleges delivering both undergraduate and graduate degree programmes. The National University remains the premiere higher education institution in the country today, and competition for entry – in part because of the heavy state subsidies for tuition – is fierce. But the expansion of private universities has been an important part of the expansion of Bangladeshi higher education over the last decade, and increasingly it is the private sector that is expected to shoulder the load of the country’s growing demand for advanced education. As the British Council has observed, "Rocketing demand for higher education has facilitated the growth of private provision as a strategy to absorb pressure on public sector places, shifting the costs of tuition away from the state, onto students and their families." There are 31 public universities in Bangladesh today but the number of private institutions is growing quickly. Estimates vary, in part due to how private institutions are counted, but there are as many as 84 private universities operating currently – the vast majority of which have been established since 2000. Private institutions enrol an estimated half million students, or roughly a quarter of the total tertiary enrolment in the country. The growing influence of the universities and their burgeoning student body was recently felt when the government was forced to abruptly alter plans to impose a 7.5% VAT (value added tax) levy on private university fees. In the face of mounting student protests, the government changed its policy so that university fees would be inclusive of the VAT, in effect meaning that the tax burden has shifted (at least for the moment) to the institutions themselves rather than the students. Up until last year, the growing influence of private university operators had also kept at bay new legislation that sought to open the Bangladeshi market to foreign providers. However, after a delay of several months, a new law was brought forward on 31 May 2014 to allow foreign universities to establish joint ventures with local partners and operate branch campuses or study centres in Bangladesh. Any such branch operations are subject to the approval and oversight of Bangladesh’s University Grants Commission (UGC) and must comply with a regulatory and licensing structure set out in the new legislation. The move remains controversial, at least within the educator sector in Bangladesh. Private providers charge that allowing foreign providers to set up local operations will weaken higher education in the country. The government for its part is confident of the quality controls in place and of the level of oversight provided for by the new law. "We will exercise caution so that no one can deceive students and no one can do business in the name of providing an education," said Education Minister Nurul Islam Nahid.