The Brazilian market for English language learning

The Brazilian government has in recent years been working to boost higher education participation, increasing demand for overseas study, and extending the reach of STEM learning (Science, Technology, Engineering, Maths), all as part of a slate of wide-ranging development goals. Partly as a result of a broad effort to internationalise higher education, the number of Brazilians studying abroad has increased by as much as 600% over the past decade. But strengthening English language acquisition for Brazilian students has been a slower process.

English in Brazil

Brazil uses English extensively in business and advertising, broadcasts English music and movies routinely, and has fast-growing tourism and trade links with the US. Considering all these facts, it would be easy to imagine that Brazil’s overall levels of English proficiency are fairly high, but according to Education First’s English Proficiency Index, the country ranks in the "low proficiency" category, as opposed to neighbouring Argentina, for example, which scores in the "high proficiency" band on the EF Index.

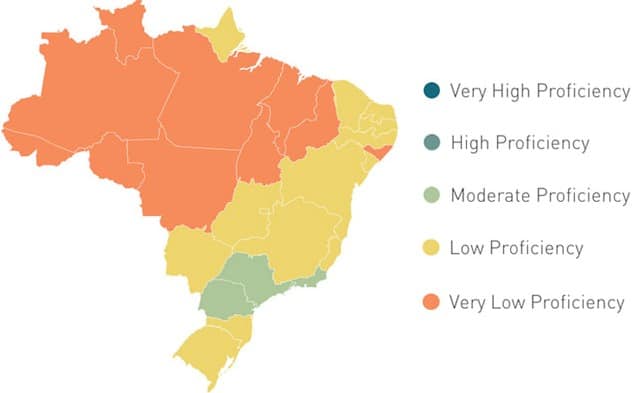

As even this simple comparison might suggest, while English proficiency has improved in Brazil over the last several years, other Latin American countries have improved more quickly still. As of 2014, only about 5% of Brazilians claimed to be able to speak English. Proficiency among that group is higher in the Atlantic South, where São Paulo and the megacity Rio de Janeiro are located.

The graphic below from EF illustrates English ability by geographic region, and highlights that no region was assessed for "very high" or "high" proficiency.

The role of national and state governments

The Ministry of Tourism has long offered such professional development programmes. Meanwhile, the national government sets broad goals such as the National Education Guidelines, and has launched important initiatives like Languages Without Borders. But these efforts cannot be as effective as a coordinated, national approach, particularly in a country as vast and culturally diverse as Brazil.

While Science Without Borders has been an unqualified success, not least because it spotlighted issues that brought about a stronger focus on English language learning, it is states and municipalities that maintain most English learning initiatives in Brazil’s heavily decentralised education system. Many of these efforts manage only limited success, according to the British Council, “due to unbalanced curriculums, limited class time, teachers lacking the linguistic and pedagogical knowledge to effectively guide students, and minimal resources.”

The National Education Guidelines offer another example of the challenge of Brazilian decentralisation. These guidelines urge public secondary schools to focus on the teaching of modern foreign languages but without singling out English. Thus, many institutions offer a slate of foreign languages. In rural communities where Portuguese is sometimes spoken as a second language after indigenous languages, English exposure is even more minimal.

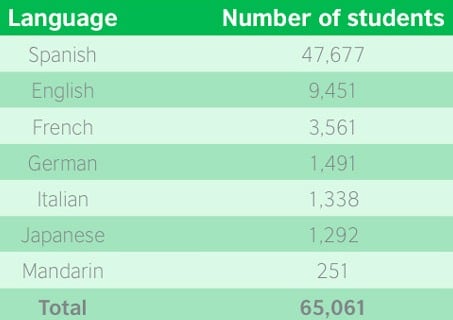

And then there is the obvious prominence of Spanish in the region as well. Centre of Language Studies data for the State of São Paulo, seen in the chart below, summarises enrolment levels in language courses for middle and high school students and reveals that English is selected at a rate five times less than that of Spanish. This is no doubt reasonable in a country surrounded by Spanish-speaking nations, however it is something of a stark illustration of where English language learning stands, even in one of Brazil’s more English-proficient regions.

The place of English

As the preceding points reflect, each of the country’s 27 territories has its own framework for foreign language teaching. The British Council’s May 2015 report, English in Brazil: An examination of policy, perceptions and influencing factors, acknowledges that these various systems are too opaque to allow for reliable information gathering. However, online surveys of Brazilians and Brazilian companies conducted by the British Council yielded a number of interesting findings, including the following:

- 82% of respondents who have not learned English say they would do so in order to improve their employment prospects.

- 61% of respondents say the reason why they do not learn English is because it is too expensive, but other reasons include a lack of time, and the perception that results take a long time to achieve.

- There is a strong correlation between level of education and English learning, as well as between income level and English proficiency. Further, English is needed more in heavily internationalised industries such as finance and professional services, and less in more locally based industries such as real estate, construction, and engineering.

- 48% of survey respondents who say they know English reveal that they learned it to improve employment prospects, but just 9% stated the skill was actually necessary for their job.

- In general, English is considered to be a luxury acquisition or an extracurricular activity, though younger people consider it increasingly valuable for personal growth.

Burgeoning demand for study abroad

New data from the Brazilian Educational and Language Travel Association (BELTA) points to an impressive 600% increase from 2003 to 2013. "In 2003, 34,000 Brazilians held abroad courses, while in 2013 there were 202,000 exchange students. Already in 2014, about 240,000 students have taken courses abroad," says the association. BELTA adds that a majority of Brazilian students abroad are between the ages of 18 and 30. When Brazilians do go abroad they prefer the US, with substantial numbers also going to Portugal, France, Germany, the UK, and Ireland - the latter country having received a boost in recent years due to increasing numbers of Brazilians opting to study there. The newspaper Irish Times described this development as "an unprecedented wave," and indeed, Brazilian applications to Ireland have nearly doubled from 646 in 2013 to 1,084 this year. BELTA points out as well that some of the recent shifts in student preferences have been toward more affordable destinations, like Canada and Ireland, as Brazilian students and parents react to the strengthening of the US dollar and Euro against the Brazilian currency, the real.

Near-term outlook

The association adds that the economy will be a big factor in determining whether the dramatic recent growth will continue at the same pace in the years ahead. "Until [2014] we had a very upward curve, but this curve will depend on the economic factors that take place in the country," said BELTA President Carlos Robles, who added, "we are seeing that the economy is in a mild downturn." However, with millions of tourists expected for the 2016 Summer Olympics, more Brazilians than ever are interested in learning English. One entity in Brazil’s private sector that has taken a leading role is Education First, which has pledged to teach English to one million citizens before the Olympics. Working in partnership with the Brazilian Olympic Committee and the Brazilian Ministry of Education, the company has made its online platform Englishtown available to 550,000 high school students and 450,000 Olympic volunteers for free. And English is more recognised as a useful skill today than in the past, mainly due to Brazil’s large population of young people who see English language learning from a fresh perspective.

Among these potential learners, factors such as lack of access, high cost, and a perception of the language as not truly needed present the biggest obstacles to widespread acquisition.

The wave of English-language tourism destined to accompany the Olympics will help demonstrate the utility of the language to Brazilians, but demand is not truly the concern. The demand is there and growing. But in vast and diverse Brazil, it is the logistical issues – central planning, funding, and access to programmes – that are likely to persist in efforts at home to build national proficiency in English. Particularly in that context, study abroad will remain a key means of language acquisition for Brazilian students going forward. But the expansion of English language teaching within Brazil, and rising concerns with respect to the affordability of study abroad, appear to be opening new opportunities for foreign providers to deliver programmes within the country as well. For additional background on this key Latin American market, please see some of our recent coverage on Brazil in the ICEF Monitor archive.