Chinese universities increasingly forced to compete for students

To say the least, higher education in China has undergone a dramatic expansion over the last two decades. The number of universities in the country has grown from about 1,400 in the year 2000 to 2,553 today. Combined higher education enrolment increased from 11.2 million in 2002 to 23.91 million in 2014. And this year alone, 7.5 million students graduated from Chinese universities and entered the job market. During most of this period, Chinese higher education could fairly be described as a “seller’s market.” There were reliably more students chasing university admission than there were seats available. In part because of this simple math of supply and demand, admissions to top universities have been hotly contested, particularly via the notorious pressure cooker of the National College Entrance Examination (commonly known as the gaokao). Under China’s domestic university recruitment system, quotas for enrolment are determined by central authorities. Applicants indicate the institutions they want to apply to and spaces are then allocated on the basis of gaokao scores. This is the mechanism through which the gaokao acquires most of its force and influence in Chinese society, and it has kept the stakes extremely high for exam takers. Do well on the entrance exams and the dream of attending a top university is within reach. But if you miss the mark on exam day, your chances are slim. Somewhere around 2008, however, the balance of power in Chinese higher education began to shift. The number of students taking the gaokao peaked that year at 10.5 million – and thereafter began a five-year decline that only began to reverse itself in 2014 when 9.39 million students sat the exam. The latest round of exams in June saw another marginal increase with a total of 9.42 million students challenging the gaokao this year.

The shrinking pool

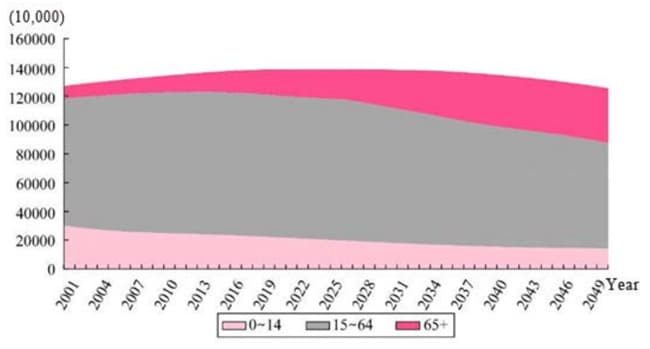

There are a couple of factors in play in the declining pool of exam applicants. First and foremost, China’s population is ageing rapidly after years of low fertility and birth rates. “In 2010, there were 116 million people aged 20 to 24; by 2020, the number will fall by 20% to 94 million,” reports the China Economic Quarterly. “As the share of young people falls and the share of elderly people rises, Chinese society will age rapidly. China already has 180 million people aged over 60, and this is set to reach around 240 million by 2020 and 360 million by 2030.”

According to the Chinese Ministry of Education, as many as one million gaokao-eligible students opted out in 2010 with about a fifth of those choosing to study abroad.

According to the latest data from the ministry, 459,800 Chinese students went abroad in 2014, an 11.1% increase over 2013. Many observers have noted that the growth in outbound mobility has been driven in part by concerns about the rigours and effectiveness of the gaokao exam, but also by concerns about quality of education at home. The Xinhua news agency quotes one apparently representative Chinese parent whose son was heading for university in the US: "For sure, China has more universities and modern campuses, but few are encouraging innovation and cultivating talents."

Competing for students

One of the effects of a shrinking pool of gaokao applicants is that many more students are able to secure a place in a Chinese university than was the case even a decade ago. Over the 1990s, the acceptance rate – that is, the percentage of those taking the exams who were admitted to university – climbed from around 25% at the start of the decade to reach 56% by 1999. That shift was fueled by the expansion of Chinese higher education during those years and the pattern persisted through the 2000s as well. As we noted earlier, the number of Chinese university spaces continued to expand from 2000 on, even as the pool of gaokao applicants started to shrink after 2008. Both factors have contributed to the national acceptance rate having reached an attention-grabbing 76% as of 2014. The declining, or essentially flat, pool of applicants combined with soaring acceptance rates point to a new reality emerging for Chinese universities. Ever more so, “the higher education sector will be forced to compete for students, in stark contrast with today's feverish competition for a place at college,” reports Radio Free Asia. This is a relatively new operating context for China’s universities and one of its earliest indicators has appeared in recent years in the form of empty seats on campus. Xinhua reports, “In central China's Henan Province, where the pursuit of higher education is intensely competitive, nearly 70,000 university or college openings were not filled in 2014, accounting for 11.36% of the province's total quotas.” 2014 was the third year in which Henan’s universities reported vacant seats, and the situation is the same in regions across the country, notably in Beijing which is home to some of the country’s finest universities. “The quotas for Beijing students who take the gaokao was cut to 52,200 in 2014, down 30% from 76,700 in 2008,” adds Xinhua, noting as well that lower-ranked universities in Beijing have reported vacancies since 2010. The increasing competition among universities spilled over to social media recently as two of the country’s leading institutions, Peking University and Tsinghua University, publicly accused each other of improper practices in attempting to recruit top students from this year’s gaokao pool. “Tsinghua and Peking generally split the top 1% of students from the gaokao,” says the news site What’s On Xiamen. “In order to enrol more gaokao winners, universities will offer abundant scholarships and free overseas exchange programmes. Some even go as far as posting pictures of beautiful alumni on their official website.” The issue of the shrinking pool of exam takers was also prominently covered in a recent report from China Education Online. This, along with other media coverage over the past few years, continues to fuel speculation and debate as to the sustainability of some institutions in the country. "Chinese universities are undergoing a serious survival crisis," said Chen Zhiwen, the site’s Editor in Chief. Other observers have argued that the real issue is that the system’s rapid expansion has led to a focus on capacity rather than quality, and that the growing competition for students will lead universities in China to more carefully examine the quality and relevance of the programmes they offer. Whatever the case, it seems clear that Chinese universities are facing a much more competitive landscape than was the case in even the recent past. The effects of this have yet to fully unfold, either in terms of domestic or international enrolment trends, but they are likely to profoundly influence both in the years ahead.