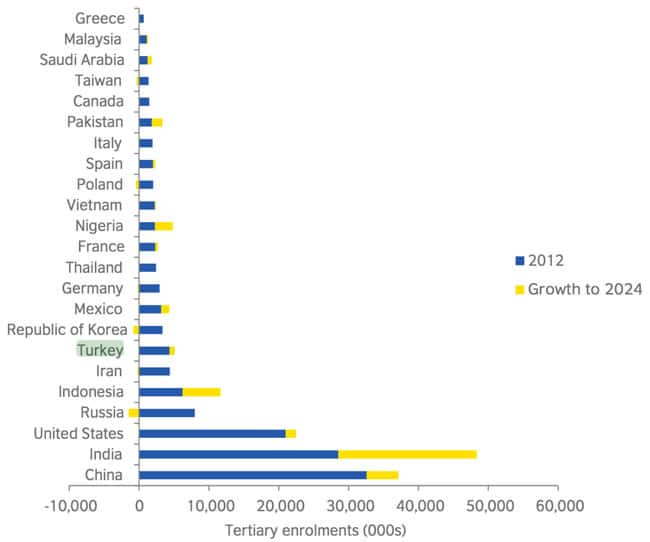

The factors driving international student mobility to and from Turkey

Last year ICEF Monitor reported on Turkey’s ambition to become an international education hub and host 150,000 foreign students by 2020. This ambition is only growing. Serdar Gündoğan, head of the Turkish Prime Ministry’s International Students Department, has announced the government’s intention to host 200,000 inbound students by 2023. Standing in the way of government plans is economic and political instability, including fallout from the civil war in neighboring Syria and widespread political and student protest. Today ICEF Monitor returns to Turkey with another detailed look at the education sector there and the challenges to overcome.

Turkey’s inbound landscape

Turkey had about 54,000 international students in 2014, with the majority coming from nearby nations such as Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Iran. However, three EU nations - Germany, Greece, and Bulgaria - are also among the top ten sending countries. Mr Gündoğan puts the number of 2014 applications from international students seeking Turkish university admission at 90,000 from 176 countries, a major jump from 56,000 in 2013, and 44,000 in 2012. In order to reach the 2023 goal, government policies are aimed not only at increasing the number of applications from abroad, but the number accepted. Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), in power since 2007, has made more scholarships available to international students. A 2012 report issued by the AKP-linked Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research (SETA) recommended this method as a way to attract more foreign students, and about 13,000 inbound internationals currently receive financial aid from the government. Still more receive other scholarships: the SETA report noted that 40% of international students in 2012 were funded by scholarships stemming from three sources: private institutions, governmental agencies, and the Turkish government’s Grand Student Program BOP. In 2014, Turkey allocated about US$96 million for government scholarship programmes, the highest amount ever. Turkey’s Higher Education Board (YÖK), also eager to bring in more international students, has liberalised its admission guidelines to be able to admit more students from conflict zones. The hope is that the number of Syrian, Egyptian, and Palestinian students in Turkey will increase. One private sector educator has taken up the specific issue of Syrian refugees by pledging US$10 million to create accredited universities for the more than 40,000 people who would be college-bound if not for the war. The government has also bolstered official education links with foreign countries. It recently made pacts with Morocco, Vietnam, and Sudan. And in late-2014 it agreed to form a Balkan Universities Association (BUA) to foster sustainable higher education cooperation in the multi-ethnic, multinational region Turkey shares with Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. While new Turkish policies have brought in more foreign students, and the number of universities has risen from 77 to 176 in ten years, critics suggest that the quality of education has fallen. Many observers and political opponents say the AKP’s approach is backward - that first the quality of education must be improved so it both functions better for Turkish students and appeals to the upper echelon of global students, and then the level of admissions should be increased. Some members of the government have admitted to quality problems. YÖK President Gökhan Çetinsaya has pointed out that each Turkish academic teaches an average of 21 students, while the OECD average is 16. He also noted that the ratio in Turkey increased to 51:1 in state universities. However, the quality of at least some Turkish universities has improved. The country has gone from no institutions listed in the Times Higher Education top 200 in 2012 to four in 2014. Ankara-based Middle East Technical University has risen all the way to 85 in global rankings.

Turkish students overseas

Turkey still sends about twice as many students abroad as it receives. Those students overwhelmingly choose Germany and the United States as study destinations, with Bulgaria, Azerbaijan, and France among the top ten. The following table shows the most recent outbound data for Turkish university students.

Turkey’s unique education issues

Turkish higher education faces many challenges. Among them is the problem of large numbers of Syrian refugees in the country. Many will remain in Turkey even when the war in Syria ends, but they face language, economic, and - as a group perceived to bring crime and joblessness to Turkish communities - discrimination barriers. If those of school age cannot continue their education, future social problems will arise. Meanwhile, Turkey’s Kurdish regions are pressing for changes to education policy as part of a wider push for autonomy. The government made concessions in 2013, among them legalising instruction in Kurdish at private schools, but Kurds want their language legalised at state schools, which are free of charge. This is no small issue, considering that Kurds are Turkey’s largest ethnic minority and Kurdish separatists are engaged in armed conflict with Turkish troops in Northern Kurdistan. Other Turkish education challenges derive from the economy. Growth was 2.5% for 2014, below AKP’s preferred level, and unemployment has reached a four-year high. According to the Turkish Statistical Institute, nearly a fourth of the jobless are university graduates (725,000 in October 2014, a steep increase from the 488,000 at the beginning of February 2014). More Turks are attending and graduating university, but this trend will only produce more unemployed if the economy cannot accommodate them. While the AKP touts its education reforms, the road has not been smooth. Some of its moves have provoked furious reactions. During the fall term a new scheme for assigning students to schools saw 40,000 students, including non-Muslims, allocated against their will to religious schools where Sunni-oriented Imam-Hatip classes were compulsory. Critics have noted a sharp rise in the number of Imam-Hatip schools during AKP’s time in power, and an 83% increase in just the last five years. Vocational training institutions have been converted for the purpose, leaving some communities with no non-religious alternatives for education. Such changes have led some to suggest AKP has a hidden agenda to “Islamicise” the nation’s schools. Government plans to build mosques on 80 university campuses add weight to these fears. The government countered by saying any religion could be represented on campuses if the demand existed. (To which students at Istanbul Technical University responded by collecting 20,000 signatures in support of the construction of a Buddhist temple.) Another AKP move that aroused negative responses gave the Higher Education Board - a government body - the responsibility for appointing the administrators of the country’s 71 private foundation universities. This essentially rendered these schools non-private by removing their ability to choose their own administrators. However the impact of reform and ongoing political conflict could generate more interest in overseas study - in a 2013 British Council survey of more than 4,800 Turkish students, 95% expressed wishes to go abroad. The main reason they did not pursue such opportunities, according to the survey, was the expense.

An election on the horizon

The future in Turkey is about to become clearer. A general election looms in June in which four major political parties will vie for 550 seats in the Grand National Assembly. All four parties speak of improving the higher education sector, but the most immediate impact is likely to occur if AKP wins enough seats to rewrite the Turkish constitution - a stated goal. AKP plans to switch Turkey from a parliamentary government to presidential one. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan suggests this would promote political stability and ease decision-making, but the change would also accrue unprecedented power to the office of the presidency. Under such circumstances opposition to AKP policies - including education reform - would weaken substantially. What Turkey has achieved in improving access to universities is nothing short of remarkable. It had one million students in tertiary education in 2000; today the number is over four million. But as the British Council and other international bodies report, the country still falls behind in quality, particularly compared to OECD and EU states. This is the issue the winner of the June election may find himself hard pressed to resolve. Editor's Note: June election results have shown that the AKP has lost its parliamentary majority and the main pro-Kurdish party has won enough votes to enter parliament for the first time. The result means a coalition government is likely.