Starting from scratch: Afghanistan continues to build its education system

In December 2001, after more than two decades of armed conflict, Afghanistan’s Taliban government was toppled and a new administration formed under President Humid Karzai. As 2002 began, the country’s education system was effectively in ruins and a massive rebuilding effort was needed to create a system that could help build a better future for Afghanistan and its people. That process of building and rebuilding has been ongoing in the 12 years since and, in some respects at least, the progress has been remarkable.

12 years and counting

Afghanistan is a landlocked country of about 31 million people in South-Central Asia. It is bordered by Iran to the west, Pakistan to the south and east (China even farther east), and Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan to the north.

- "nine years of basic education will be compulsory for all Afghan children (boys and girls) between the ages of six and fifteen years old;

- secondary, technical and vocational education and higher education will be expanded;

- education in state schools and institutions will be free up to university level;

- special reference is made to the elimination of illiteracy and promotion of education for women;

- the establishment of private general, technical and vocational and higher education will be allowed and regulated by the law.”

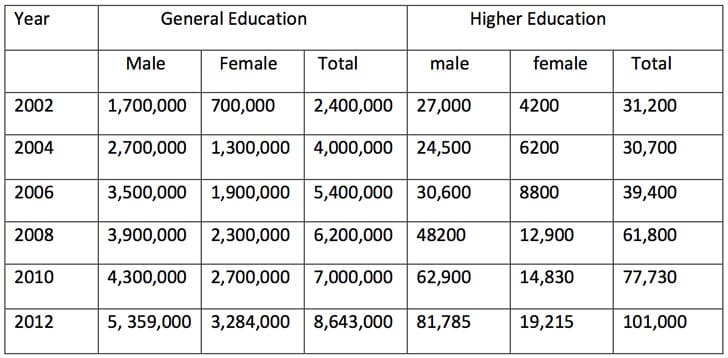

Dr Samady’s paper also charts the dramatic growth in enrolment within Afghanistan from 2002 on. Enrolment in general education increased from an estimated 2.3 million students in 2002 to 8.6 million in 2012 - roughly 38% of which (3.2 million) were female.

Participation in higher education has grown at a similar pace, rising from 31,203 students in 2002 to 101,000 students in 31 public universities and institutes (and another 20,000 students in private institutions) as of 2012. Participation by female students, however, drops to about 19% at the university level.

Rounding out the picture, a 2011 study estimated the enrolment in technical and vocational education and training (TVET) programmes at a further 350,000 students across 600 public, private, and non-governmental organisation (NGO) training centres.

Outbound student mobility

The UNESCO Institute for Statistics reports that the number of Afghan students studying abroad grew from 2,956 in 2002 to 9,754 in 2012. Mobility statistics are often tricky to nail down and especially so for a country like Afghanistan where historical data may be incomplete or simply unavailable. Published estimates of the current numbers of students abroad range from 10,000 (as per the UNESCO statistics) to as many as 15,000. Most sources, however, agree that leading destinations for Afghan students include Iran, India, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia, followed by a range of host countries in Europe and the west. There is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that Iran has been less in favour in recent years due to more stringent student visa requirements. India, meanwhile, remains a popular choice due to both its proximity and affordability. As Al Jazeera reported in 2013, “Low cost of living, scholarships, familiarity with the country's culture and language, good relations between governments, easy-to-obtain visas, and the use of English in the classroom are some of the main reasons Afghans like to study in India.” However, the report adds, “Those who can afford [to do so] go to Europe and the United States to study.” As the four-fold increase in outbound student numbers over the past decade would suggest, the demand for high-quality education continues to grow within Afghanistan.

This is clearly a market, however, for which affordability is a key issue and whose economic prospects will no doubt play a big role in shaping demand for study abroad in the future.

In the near term, the World Bank is projecting a sharp reduction in GDP growth for 2014 and 2015, largely as a result of reduced in-country spending as foreign governments withdraw their armed forces. However, as an East Asia Forum column from last year points out, “Afghans emphasise they are a youthful and resilient population. The economic growth of the last year or two has not just depended on security, it has been the result of long-term investment in infrastructure and agriculture… Most of all, Afghans are determined that their hard work of the last 20 years has not been for nothing.”

Back to the quality question

Another major factor in the future demand for study abroad will be the quality of education at home. On this point, Dr Samady concludes, “The quality and efficiency of education continue to be a challenge (shortage and quality of teachers and faculty, lack of adequate physical and learning facilities including laboratories and libraries, out-dated curricula and lack of suitable textbooks, especially in vocational and higher education, absence of a comprehensive national strategy for science and technology and vocational training)… There is [however] a strong and growing demand for modern education and training for boys and girls in Afghanistan. The aspiration of the majority of Afghan people is for a better life, especially for their children.”