Updated: Finnish government backs away from plan to introduce tuition fees for non-EU students

Finland will remain - along with Germany, Norway, and Iceland - one of the four European countries that do not charge tuition fees for university studies. In what has been characterised by Finnish broadcaster YLE as a “u-turn on tuition fees” the government has backed away from a plan to introduce fees for students from outside of the European Economic Area (EEA). The issue has now been referred to a ministerial working committee for consideration, and it is unclear when or how the government will revisit the issue in the future. The question of tuition fees for non-EEA students in Finland came back into public view in October with a government proposal tabled by Minister of Education, Science and Communications Krista Kiuru. Under the plan outlined by the minister, Finland would have introduced tuition fees for non-European students as of 2016. The October proposal was, to say the least, unexpected. While the question of international tuition has been regularly debated in the Finnish parliament in recent years, it has not received strong support in political or academic circles. Indeed, earlier proposals to raise fees for students from outside the EEA have been widely panned by student groups in Finland. And a pilot project to levy fees at 19 Finnish institutions concluded earlier this year with no strong findings in favour of international fees, and little apparent enthusiasm for the subject among participating universities and polytechnics. Minister Kiuru’s proposal would have seen fees apply for students from outside the EEA - that is, outside of the 28 European Union members as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway - beginning in 2016. While institutions were expected to have discretion in setting their own fees, the government proposal prescribed a minimum tuition of €4,000 (US$5,000) per year, to apply only for degree programmes taught in languages other than Finnish or Swedish. Exchange students would not have been affected by the proposed policy.

Inbound mobility today

Finland hosts roughly 20,000 international students today, including both exchange students from within Europe and visiting students from beyond the EEA. Roughly half of them stay on to work and contribute to the Finnish economy following their studies. A recent item in University World News quotes, in translation, from a preliminary report on the impact of international students in Finland prepared by the Ministry of Education’s Centre for International Mobility, “The reported Statistics Finland figures show that, during the last ten plus years, the number of foreign students in Finland’s higher education institutions has tripled, being almost 20,000 in 2013. In particular, the numbers of students originating from Asian and African countries have increased substantially in recent years… Of the foreigners [who] graduated in 2011, more than two thirds were still in Finland a year after graduation, while two thirds of the ‘stayers’ were in employment.” The most recent figures from UNESCO indicate that Finland hosted 17,636 foreign students in 2012, with the top 15 source countries accounting for nearly 70% of that enrolment as follows:

- China (2,129 students);

- Russian Federation (2,107);

- Nepal (976);

- Nigeria (939);

- Vietnam (904);

- Estonia (772);

- Pakistan (603);

- Bangladesh (591);

- India (557);

- Sweden (556);

- Germany (525);

- Ethiopia (454);

- Iran, Islamic Rep. (401);

- Kenya (388);

- Ghana (382).

Non-EEA countries, particularly those in Africa and Asia, account for a surprising percentage of total international enrolment. In fact, non-EEA markets in the top 15 source countries outlined above account for about 60% (10,431) of all foreign students in Finland.

How to shelve a proposal

The Finnish government has sent its tuition proposal out for review by the country’s higher education institutions, and, as news outlet YLE reported in late-November, “It now appears that universities and polytechnics in the country are agreeing to the motion, as a comment round organised by the Ministry of Education and Culture shows that they predominately approve… A number of higher education institutions in Finland support the implementation of tuition fees, but wish to keep the authority to collect and determine the tuition amount themselves.” However, subsequent reporting from YLE this month announces that, “The government parties could not reach agreement on the issue after the proposal was sent out for consultation… Defence Minister Carl Haglund said that there was no unanimity on the matter and that he personally was sceptical about the supposed benefits of charging for tuition.” Samu Seitsalo, Director of the Centre for International Mobility (CIMO), had earlier added a broader perspective as to the potential economic impacts of the tuition policy: “From a university and polytechnic perspective, it is a positive move, as it would mean more money for the institutions. As long as the proportion of people coming to study remains the same and the state continues to pay its part, the universities can use the tuition fees as they see fit. In terms of the national economy, however, it is a trickier issue. How that plays out will be largely dependent on how many students come to Finland from outside the EU and the EEA after tuition fees are implemented.” Student groups and faculty associations, meanwhile, have been firmly opposed and question the underlying business case for introducing fees for international students. Jarmo Kallunki is the education policy officer at the National Union of University Students in Finland and, he, for example, had laid out a detailed case against the introduction of international fees in a recent guest column for University World News where he:

- questioned the competitiveness of Finnish education relative to other international destinations;

- outlined the current economic impacts of foreign students in Finland;

- argued that the introduction of fees for non-EEA students would “cause international student numbers to plunge” - with a corresponding decline in the foreign capital contributed by students for living expenses;

- and explored the longer-term impacts of students staying on in Finland after their studies.

In part, both Mr Kallunki and Mr Seitsalo were reflecting on the same question: to what extent could the introduction of tuition fees cause non-EEA enrolment in Finland to drop? In this respect Finland has a close-to-hand example to consider in the case of Sweden, and Sweden’s experience may have been an important element on which the debate in Finland turned.

A cautionary tale

Sweden introduced fees for non-EEA students in 2011 and non-European enrolment in the country promptly plummeted.

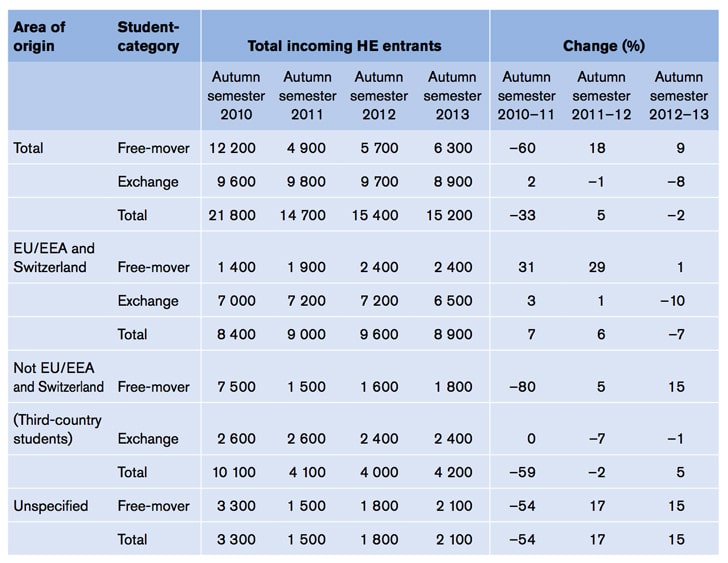

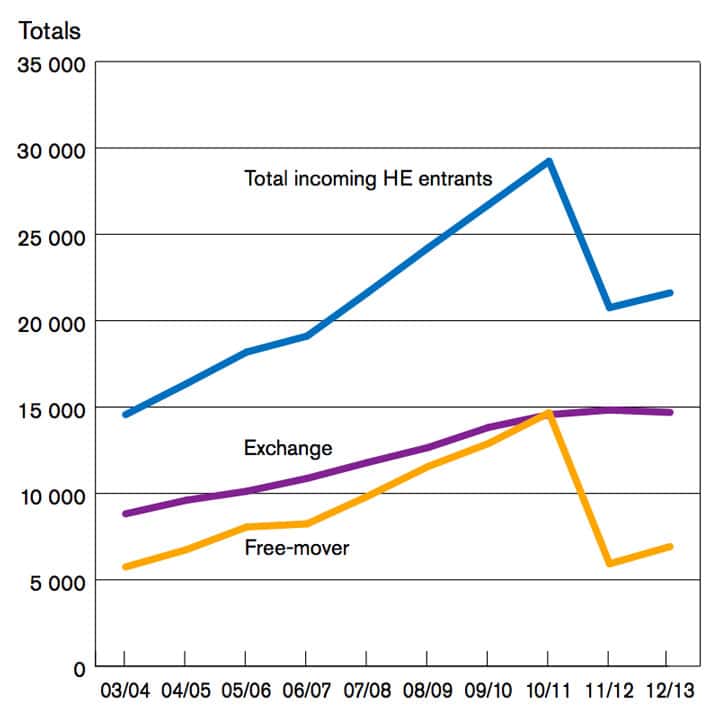

The Swedish Higher Education Authority reports that non-EEA enrolment in Sweden dropped roughly 80% from fall 2010 to fall 2011 (the point at which international fees were introduced).

As the following table reflects, non-European enrolment has recovered modestly in the years since, in large part due to the recruitment efforts of Swedish institutions (and the country’s international education bodies) and with expanded scholarship support for visiting students.

Please note that the term “free mover” is used in the table to indicate students who come to Sweden outside of a formal exchange programme (including non-EEA students which accounted for about 61% of “free movers” in Sweden in fall 2010) and are therefore more likely to have been affected by the introduction of foreign student fees.

Most Recent

-

British Council says student recruitment to UK higher education will get a boost this year from South Asia and the “Trump effect” Read More

-

New Zealand expands post-study work opportunities for international students Read More

-

As Iran retaliates across the Middle East, schools close, students worry, and institutions reassess transnational education Read More