Report highlights imbalances in degree mobility within Europe

A recent report commissioned by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy (Global trends in student mobility

The number of internationally mobile students worldwide continues to grow rapidly. Earlier this year, we reported that the number of students moving between countries to study is likely to approach five million in 2014.

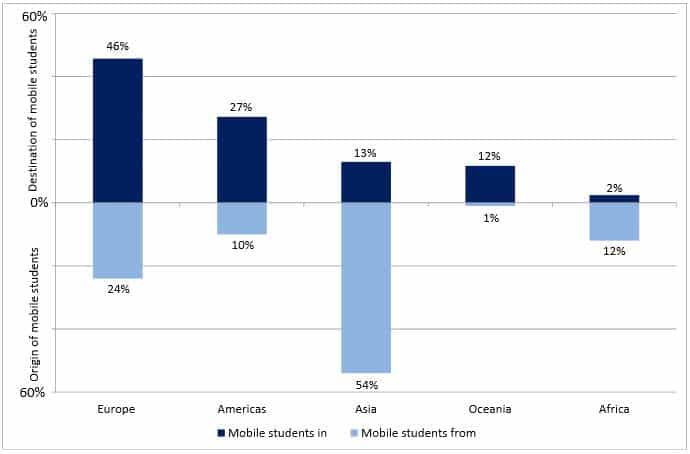

The EHEA report notes that in 2010, nearly three million degree-seeking mobile students were reported to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, representing about 2% of the worldwide student population. Almost half of all globally mobile students study in a European country, with a quarter studying in the Americas. One in five mobile students choose a host country in Asia or Oceania, while only 2% study in an African country.

Interestingly, while European countries host 46% of mobile students worldwide, European students represent only 24% of the world’s outbound mobile student population. European countries as a whole are thus considered net importing countries, receiving almost two times as many students as they send.

In comparison, the region defined as Oceania - primarily Australia and New Zealand - boasts an even greater import-export ratio. Countries in Oceania receive 17 times more mobile students than they send abroad.

For Asia, the imbalance skews in the other direction. While Asian countries account for fully 54% of globally mobile students, they host only 13% and are thus considered exporting countries.

European mobility trends

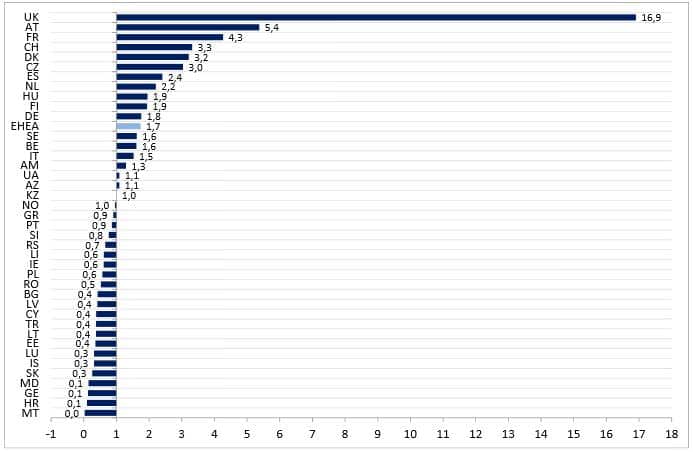

Some of the richest data in the report highlights imbalances in mobility between specific countries. For example, the UK, Austria, France, Switzerland, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Spain, and the Netherlands are above-average net importing countries, sending far fewer students abroad than they receive.

Hungary, Finland, Germany, Sweden, Belgium, Italy, and Armenia are also considered net importers, though their import-export ratios (a measure derived by dividing the net incoming mobile students by the number of outgoing mobile students) tend much closer toward the EHEA average.

Meanwhile, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Norway, Greece, and Portugal have relatively balanced import-export levels. (Data for Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Holy See, Montenegro, Macedonia, and the Russian Federation is incomplete as those countries did not report their numbers of incoming mobile students.)

Imbalances probed

While the ministers responsible for higher education in the EHEA encourage the member countries to work towards more balanced mobility, the report notes that the desirability of achieving balance (or maintaining a current imbalance) in mobility can differ depending on the perspective of the country. Policy goals at the state or institutional level, for example, as well as economic trends and other factors influence the degree of imbalance.

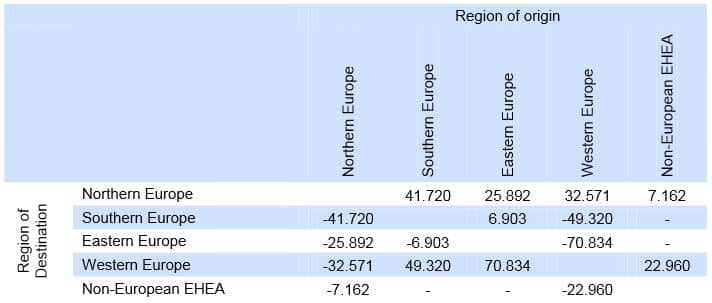

Imbalances can also be observed between specific geographical regions, with Northern European countries (Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, UK, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia) and Western European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Switzerland) classified as net importing regions, whereas Southern, Eastern, and Non-European countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Turkey) within the EHEA are net exporting regions.

Northern Europe hosts far more incoming mobile students from elsewhere in the EHEA than it sends students to other regions. The report also found that mobile students from Southern, Eastern, and Non-European EHEA countries in Western Europe significantly outnumber outgoing mobile students from Western to Southern, Eastern and Non-European EHEA countries.

Better data, please

The report concludes with a call for improved data collection that would allow future research to study imbalances in certain fields of study, across geographic regions within countries (for example, border regions or capital cities) and in specific language zones of a destination country (e.g. French, Italian, German mobile students in Switzerland).

These proposed additions, say the study’s authors, would provide a more nuanced picture of mobility within the region and highlight examples of imbalances at the sub-national level.

In closing, a quick note on the methodology for the current study. The report looks at two types of mobility imbalance:

For the sake of greater clarity in the more compact summary we have provided here, we have focused on absolute imbalances in today’s post. Readers who would like a closer look at calculations and observations concerning relative imbalances are encouraged to consult the full report.