Market Snapshot: Mongolia

Bordered by Russia to the north, and China everywhere else, Mongolia is a landlocked country nearly twice the size of Eastern Europe. With a population estimated at just over three million, Mongolia is the least populous nation in the world. About half of its people, however, are based in the capital of Ulaanbaatar.

Mongolia is increasingly on the radar for international recruiters as an emerging market in the region, fueled both by strong economic growth and by the aspirations of its people. Today ICEF Monitor takes a closer look at Mongolia, its history, its future, and its education market.

Mongolia 101

The country came under Soviet influence and was effectively established as a Soviet satellite state in 1924. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Mongolia reconstituted itself under a democratic, multi-party system in the early 1990s and began a transition to a market economy. And what a transition it has been: Mongolia has possessed one of the fastest-growing economies in the world in recent years, thanks mainly to its burgeoning mining sector. But earlier forecasts that the country’s GDP growth would reach 15% in 2014 have not materialised. First-half growth for the year is way off that earlier projection, and growth has unquestionably slowed in 2014. “Mongolia’s economy expanded 5.3% in the first-half of 2014, the weakest pace since 2010,” reports Bloomberg. “As recently as 2011, Mongolia grew at a world-beating 17.5%, before slowing to 12.4% in 2012 and further to 11.7% last year. The currency, the tugrik, slumped 16% in the past year to a record low of 1,897.73 on August 14 and inflation jumped to 14.9% as of the end of July.” However, even the previous years of high growth and an estimated mineral wealth of up to US$1.3 trillion never translated into economic gains for the entire population. The World Bank estimates that about 25% of Mongolians live under the poverty line. Thanks to government investment, access to education has improved in the last two decades, and policymakers hope wider access will eventually relieve poverty.

High demand for education but low levels of spending

During its years under Soviet influence, the schooling from primary level through university was free for all students in Mongolia. The dissolution of the Soviet Union meant financial support for education disappeared, sending education systems into a steep decline that bottomed out in the early 1990s.

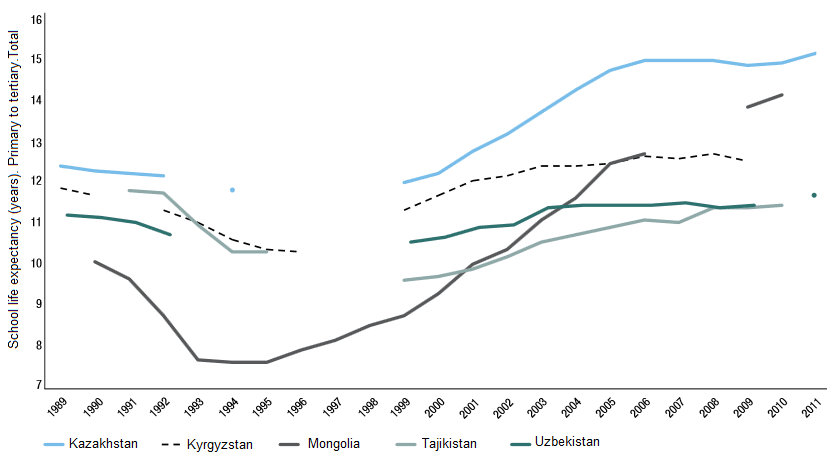

In 1994, the average length of time spent in school by Mongolian students was 7.7 years, but by 2010 that span had increased to 14.3 years. During roughly the same period, the number of students going on to tertiary education increased by six times. Development Progress, a UK-based research group, reports, “Almost three in five Mongolian youths now enroll in university – a rate comparable to the average for high-income countries.” These shifts saw Mongolia improve from the lowest school life expectancy in Central Asia to second, just behind Kazakhstan.

The education system today

The 2013/14 Global Competitiveness Index offers a set of figures concerning Mongolian higher education. Ranked alongside 148 other countries, Mongolia scores:

- 43rd in gross tertiary enrolment;

- 68th in quality of math and science education;

- 73rd in extent of staff training;

- 83rd in Internet access in schools;

- 136th in quality of management of schools;

- 137th in overall quality of the education system.

Students entering the Mongolian tertiary sector have a choice of 178 colleges, universities, and teacher training colleges, of which 42 are public. These schools are administered by the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science, which sets policy and oversees standards. As of 2013/14, Mongolian colleges and universities enrolled a total of 174,075 students, the vast majority of which were studying in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar. In total, 18,063 of those students were in Masters programmes, while 3,304 were working toward PhDs. Technical and vocational schools, conversely, have seen student numbers decline recently with a combined enrolment of 42,800 in 2013/14, down from 45,200 during 2010/11.

Education-employment mismatch

While university enrolments are high, the country’s higher education graduates are not sufficiently competitive in international markets. The number of graduates surpasses the available employment opportunities, and because demand for skills in the mining-dominated economy is not matched by supply, graduates of Mongolian universities face difficulties finding employment. A World Bank study from 2010 showed that only a third of university graduates found jobs, compared with two thirds of technical and vocational graduates. A 2011 UNESCO analysis seems to confirm the World Bank’s conclusions, suggesting that Mongolian curriculum is not well aligned with modern education standards. In addition, concerns abound regarding whether degrees bestowed by Mongolian higher education institutions meet global standards. The Mongolian government is aware of such problems, though, and has announced plans to realign its education system toward the country’s market economy. Minister of Education and Science Luvsannyam Gantumur told the European Times earlier this year that the government wishes to “partner with local and international companies concerning creating internships for our students to allow them to gain practical experience in different fields.” The Minister added, “We want to foster a new generation of Mongolian youth who make the most of their individual talents and get involved in research, business and other activities which will support the country’s on-going development. We believe that foreign companies in Mongolia can play an important role in this effort.” There are indeed indications that foreign influence on Mongolian education has increased during Minister Gantumur’s watch. In October 2013, for example, a model classroom incorporating Japanese-style technical education opened at the Institute of Engineering and Technology in Ulaanbaatar, using curriculum from Tomakomai National College of Technology in Hokkaido, and hosting two Japanese professors from the Tokyo Metropolitan College of Industrial Technology. Another example of Mongolia’s international outreach is the Mongolia-Germany Institute of Technology, established in 2012 through a memorandum of understanding with the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ). Such agreements may increase, as Minister Gantumur has said that the government seeks international partnerships in the education sector, but at the moment only about 500 Mongolians study in foreign-affiliated universities or colleges.

International mobility trends

English language proficiency among Mongolian students is growing, and the number of students who are both financially and academically capable of studying abroad is projected to increase in coming years. As in the higher education sector, there has been an expansion of private-sector language schools in Mongolia in recent years. However, the level of training available does not match up well with industry requirements. The major subject areas in demand within Mongolia, as estimated by the Economic Research Institute (ERI) and the National University of Mongolia, are:

- Business administration (22.7%);

- Marketing management (15.6%);

- Accounting (12.1%);

- Finance and economics (11.9%);

- Computer science (7.2%).

In other words, the vast majority of Mongolian higher education students are interested in studying business.

Interestingly, Education USA reports that in terms of Mongolian students in the US, “Top fields of study include engineering, technology, natural sciences, teaching and agriculture. The Mongolian government has indicated an interest in providing financial support for study in these areas.”

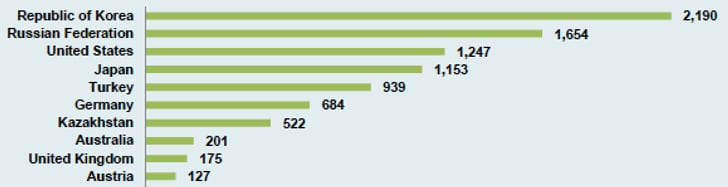

UNESCO estimates that there were just under 10,000 Mongolian students enrolled in higher education abroad in 2012. Leading destinations include South Korea, Russia, the US, Japan, and Turkey.

Looking ahead

With 21% of the population aged 15 to 24 years, almost universal literacy, high enrolment in tertiary education, and growing access to communication technology, Mongolia’s international education market appears poised for growth in the years ahead. But government policy and national economics will have to continue to combine in a positive way for that growth to be sustained.

Most Recent

-

As Iran retaliates across the Middle East, schools close, students worry, and institutions reassess transnational education Read More

-

US: Student visa issuances fell by -36% in summer 2025; OPT uncertainty among factors affecting international student demand Read More

-

Canada and India deepen educational ties; India repositions as an equal player in international education Read More