As Royal Society calls for changes to UK schools, demand for British education remains strong

A new report released by The Royal Society calls for sweeping reforms to how science and mathematics are taught in British secondary schools. The proposed reforms are designed in part to encourage more British students to enter STEM (science, technology, engineering, maths) fields at the post-secondary level and to fill future projected jobs shortages in science and technology-related fields. The Royal Society is the national academy of science in the UK and is comprised of distinguished scientists drawn from all areas of science, engineering, and medicine. The report, Vision for science and mathematics education, set’s out the Society’s ideas for science and mathematics education in the UK over the next 20 years. The report was authored by a committee of distinguished members of the teaching and science professions. As part of the consultation phase in the lead up to the final report, a process that began in 2012, committee members engaged broadly with members of the scientific and teaching communities, as well as the wider public. According to committee chair Sir Martin Taylor, the report aims to endow students and citizens with the ability to engage more deeply and for a longer period of time with science and math-related fields. "We want inspirational education systems that will deliver both scientifically and technologically informed, engaged citizens and appropriate numbers of qualified people who wish to take up science and technology-based careers,” he said. “Science and mathematics are at the absolute heart of modern life. They are essential to our understanding of the world.”

Key recommendations

One of the key recommendations outlined in the report is the introduction of baccalaureate-style frameworks within the education system, incorporating “inspirational science and mathematics curricula” and emphasising practical work and problem-solving through to age 18. A second key recommendation is the need to stabilise curricula and assessment in order to further support excellence in teaching and learning. To this end, the committee calls for the introduction of new, independent expert bodies in England and Wales and for strengthened bodies in Scotland and Northern Ireland in order to better leverage the expertise of distinguished STEM professionals. Finally, the report calls for strengthened professional development for, and recognition of, teachers, particularly with respect to subject-specific training in STEM fields. The committee recommends that primary schools should have access to at least one subject teacher in both science and mathematics. At the secondary level, mathematics and sciences should be taught by teachers with relevant degrees. Speaking to the BBC, report co-author Dame Alison Peacock, head of the Wroxham School in Hertfordshire, said: "Teaching is a chronically undervalued profession in the UK. Our country's future prosperity rests in teachers' ability to inspire and guide our young people, yet we don't currently adequately recognise or reward them.” Other recommendations include:

- Expanded opportunities for students to engage with STEM role models and consider STEM careers;

- An improved role for teachers in assessing student achievement in public qualifications;

- Enhanced collaboration and communication between and among science and mathematics education researchers, scientists and mathematicians, teaching professionals, policy-makers and the public.

New skills for the jobs of tomorrow

For Dame Julia Higgins, vice-chair of the committee, the changes proposed by the report are required to better prepare British students for the future. “Estimates suggest that 1 million new science, technology and engineering professionals will be required in the UK by 2020 and yet there is a persistent dearth of young people taking these qualifications after the age of 16,” she said recently to TES Connect.

Additional reforms already underway

Earlier reforms to British upper secondary curricula are just now coming on stream. New GCSEs (General Certificate of Secondary Education) and A-levels recently published by the Department of Education are designed to “prepare pupils for life”, according to a recent article in The Telegraph. The overhaul, like the Royal Society’s recommendations, are designed to place greater emphasis on developing the higher-level skills British teenagers need at university and in the workplace. A-level mathematics students, for example, will now need to interpret at least one large data set, part of a focus on interpretation and problem-solving skills. Foreign language students will learn more about relevant sociological and cultural issues in order to deepen their understanding of countries where certain languages are spoken. These changes are on top of new A-level syllabuses already published by the Department of Education for subjects such as history, science, and English. According to a spokesperson at the Department of Education quoted by The Telegraph, “Our top to bottom reform of GCSEs and A-levels will mean young people are leaving school with the skills they need to secure a good job, an apprenticeship or a place at university. These rigorous new exams will equip our children with the best skills and education so they can fulfill their ambitions and succeed in a global workforce.”

Demand for British education remains strong

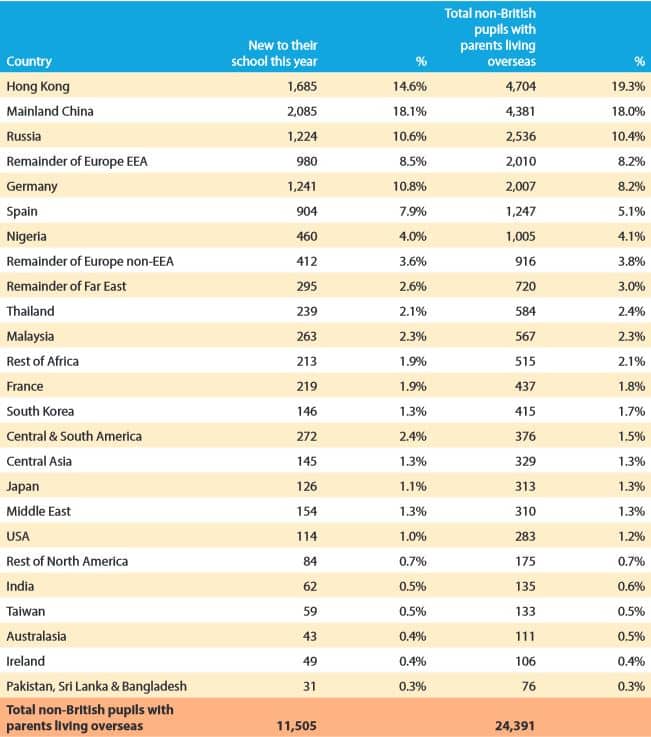

Despite the debates regarding curriculum and priorities at home, international demand for British education remains robust, according to a recent article in Forbes highlighting the continuing allure of a British education for international learners, a topic we have covered previously. The article quotes a recent report produced by the Independent Schools Council (ISC), the umbrella organisation for fee-paying students in the UK, that shows that nearly one in five boarding students at member schools are non-British pupils with parents living overseas. The largest numbers of these students (as of January 2014) come from Hong Kong, China, and Russia.

London attractive for Indian post-secondary students

Another recent survey, this one focused on the post-secondary sector, found that the vast majority (85%) of Indian students studying in London believed that a London education widened horizons and gave the opportunity to explore a greater choice of careers. The survey was carried out by the London University International Partnership (LUIP), a group of 17 London universities who work to promote the city as the best place in the world to study. In total, the survey covered respondents from a third of the city’s universities and found that an average of £2.5 million has been awarded in scholarships to students from India each year, and over £7 million over the last three years. Speaking to IBN Live, Kevin McCarthy, head of studylondon.com, said, "London is home to over 105,000 international students from 220 nations. Students studying in London not only replicate London's diversity but also contribute hugely to the city's vibrancy."