English universities record first international enrolment drop in 29 years

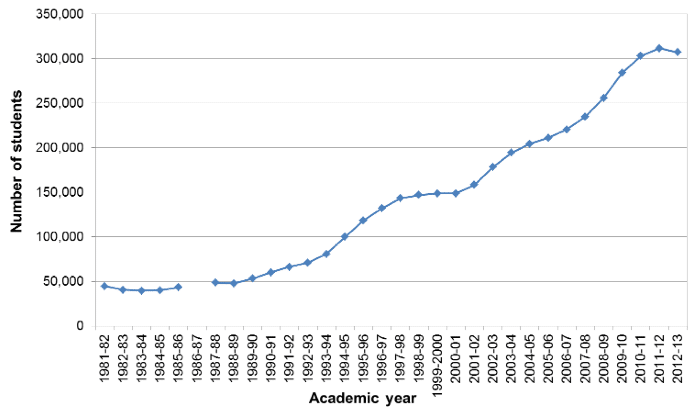

Since 1994/95, when the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) began collecting data on international enrolments in UK higher education institutions, there has never been a decrease in enrolments – until now. The Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) has announced that first-year international student enrolments at English higher education institutions fell by 1% in 2012/13 – the first drop in 29 years.

The most drastic decreases in student numbers can be seen in the post-graduate area, particularly among students from India and Pakistan. Overall first-year Indian numbers across the English higher education system fell by 26% in 2012/13 (from 16,335 the previous year) to 12,280; the decline among Pakistanis across the system was 17%. As we will see later in this article, the Indian–Pakistani fall is particularly acute at the post-graduate level.

At the undergraduate level, international entrants actually grew by 3% in 2012/13, but there was a sharp decline from students from other EU countries. The EU-student decline is probably due to the increased tuition fees they must pay in England (the maximum level of tuition fees rose from £3,465 to £9,000) paired with an inability to access the same student loans as English students.

Overall first-year drop is particularly troublesome in England

The HEFCE analysis shows that new entrants into the English higher education system represent a larger proportion than they do in other countries. New entrants into English higher education institutions in 2012/13 represented 53% of the total international and EU enrolments (65% for post-graduate enrolments) compared to 38% in Australia, 31% in the US, and 33% in Germany. Thus when new entrants decrease, as they have in 2012/13, the English higher education system suffers a bigger blow than it would be in other countries. As HEFCE points out, English courses tend to be shorter, thus they require more recruitment effort to maintain student flows – and crucial to recruitment success is a country’s visa and immigration policies and processes. As we have reported on for some time now, Britain’s immigration policies have been seen to be adversely affecting international students (e.g., international students have been lumped into net migration reduction targets) and many international students have developed a viewpoint that Britain is not a welcoming study abroad destination anymore. The British government did do some work to redress this in 2013, but the HEFCE report shows that it may not have been enough to offset the perception. Also in context, the overall international student drop in England comes at a time when British higher education institutions are also coping with a decline in enrolments from domestic students.

Biggest sources of decline

The largest sources of the overall drop are:

- As mentioned earlier, full-time EU undergraduates fell by almost a quarter in England to 17,890 in 2012/13. EU students can find much less expensive undergraduate programmes in many other EU countries, so it will be interesting to see which countries end up as beneficiaries of England’s loss.

- And again, there were massive declines registered in Indians and Pakistanis enrolling in English post-graduate courses (-51% and -49%, effectively). Interestingly, HEFCE notes that the US saw a 10% increase in post-graduate students in 2012/13, with growth coming mainly from India (40%). Australia, similarly, enjoyed 66% more Indian student commencements and 46% more Pakistani ones across its higher education system in 2013/14. So Indians and Pakistanis are still going abroad for study, but they are pursuing options other than the UK.

- International entrants to full-time undergraduate STEM courses fell by 8%). Within this overall drop, computer sciences shouldered the biggest hit (-35%), while maths and sciences fared much better with growth of 18%. Please see our past article for the British STEM sector’s large reliance on international students for their existence.

Biggest areas of growth

HEFCE reports that undergraduate students from Hong Kong – who could not be accommodated in local schools (see this article for more on Hong Kong) – and from Brazil – who more than doubled to reach 500 largely as a result of the Science Without Borders programme – were positive factors in England’s overall higher education enrolments. According to overall immigration data (which does not separate higher education from other areas of English education), China, Hong Kong, and Malaysia are continuing to drive international enrolments in Britain. HEFCE points to Malaysian growth being in part attributable to a simplified visa application process for students seeking study at universities with “highly trusted sponsor status” in 2012 (again, pointing to the huge significance of a country’s visa policies to its popularity as a study destination). Chinese students, who are the largest group of international students at UK universities, grew by 6% (56,535) in 2012/13. There was a surge in Indonesian students (albeit from a low base) being issued British visas between July and and December 2013. The expectation is that this growth is related to the Indonesian-UK DIKTI scholarship programme for post-graduate students, primarily at doctoral level.

Huge percentage of international students studying at the masters level

As HEFCE reports, the number of full-time taught masters entrants not from the UK (including other EU and international countries) has grown from 66% in 2005/06 to 74% in 2012/13. HEFCE notes: “There is therefore increased exposure of this aspect of post-graduate provision to changes in international demand.” If more masters-level international students decide that the UK is projecting too unwelcoming an image – as many Indian and Pakistani students seem to have done recently – this sector of the higher education system in England will be in for a tremendous hit, given the huge international composition of its student body. And yet, the British government has removed the right to work for two years after graduation for international students. Instead, as Times Higher Education reported in 2013:

“Since April 2012, non-European Union graduates looking to stay on to work in the UK after their studies have four months to find a job paying at least £20,000 at a registered sponsor company that will support their application for a Tier 2 visa.”

The UK’s immigration policies also have a context: a global one. University World News reports a concern that for the UK – and universities in England – this decline “takes place against a background of increasing demand for transnational education globally, suggesting that the UK's place among the leading destination countries may be under threat.” HEFCE itself concludes that with the continuing globalisation of education, competition from a "wider range of countries" is very likely to increase:

"Higher education institutions, sector bodies (including HEFCE) and government need to continue to nurture and support England's international engagement in education. The creation of an enabling environment for collaboration with a wider range of countries in research, teaching and knowledge exchange is emerging as a key determinant of whether higher education in England continues to be a key global player."