China’s slowdown doesn’t mean the sky is falling

Newspaper headlines across the world have been filled of late with the news that China’s gross domestic product (GDP) slowed to 7.7% for the first quarter of 2013, due in large part to lower growth in the country’s industrial sector. The GDP growth is not lower than in many other countries (in fact some have called it “enviable”) and it is on target with the Chinese government’s target for the year of 7.5% growth – but it has nonetheless rung alarm bells on trading floors across the globe:

“Commodities from crude oil to copper, wheat and corn all fell after the data, share prices were knocked lower and the Australian dollar slid as investors repriced expectations of import demand from China.”

The Chinese economy is the second largest in the world and its 10%-and-above growth rate in the first decade of this century was a valued driver of the global economy in uncertain times, especially with the onset of the global financial crisis in 2007/2008, and particularly for heavy commodity exporters. China is now the world’s largest trading nation, surpassing the US in this capacity last year. However, despite the fact that slowing Chinese industrial growth will indeed have some adverse effects on some sectors and countries, not all the news is bad. In fact, many analysts are saying the slower growth in the Chinese industrial sector is:

- inevitable,

- necessary for the maturation of the rest of the economy,

- required for sustainable development.

In this article, we look to some of these viewpoints since they may provide a sense of how important economic and social shifts now taking place will affect this key market going forward.

Chinese economy is maturing

In 2011, Professor David Beim at the Columbia Business School summed up the Chinese economy in the 2000s like this:

“For 30 years, China’s mix of entrepreneurial energy, heavy investment, and low-wage exports has proven such a potent formula that many, both inside and outside China, cannot imagine it slowing down. But sustained high growth is being undermined by inflation, declining returns on investment, and rising bad loans in the banks.”

Professor Beim wrote that the required solution was domestic consumption – making sure more Chinese consumers could have the means and standard of living to afford its “prodigious” consumption. He commented: “If domestic consumption is to be China’s saving grace, wages need to increase substantially and the famously high savings rates of individual Chinese will have to come down. That requires better state healthcare and more affordable education, so that the Chinese people do not have to save money to shoulder these costs on their own. "The entire development philosophy needs to shift away from producers and toward consumers, with businesses raising wages and banks raising deposit rates and increasing consumer loans. However, there is a timing problem: raising wages will impact export competitiveness immediately, but the benefits of wealthier consumers buying more will take many years to evolve.” In short, Beim was arguing for a more nuanced, gradual, and comprehensive approach to fiscal management – not one that would make for splashy headlines, but one that would provide better access into the economy for more Chinese over the long term. In other words, for the Chinese economy to grow sustainably over time – with the support of its huge population – the focus would have to shift from GDP to a wider range of indicators, including quality of life. Social wellbeing is key to economic and political stability, and right now, according to some China watchers, China has a long way to go to improve on this front. As Marguerite Dennis writes on the MJDennis Consulting blog:

“The gap between the rich and the poor continues to widen …. Chinese families worry about unemployment, health care, retirement, the environment and their children’s education. Clean water is a national issue as is health care.”

The fact is that industrial output alone does not an economy – or great world power – make. The expansion of production and manufacturing can go on for only so long before other parts of the economy and society need to catch up – not to mention its domestic consuming base, as Professor Beim asserts. Canada’s Globe and Mail explains that: “China’s service sector is finally beginning to catch up to industrial production as a share of GDP, now making up slightly under 45%. The fraction is still well behind mature Western economies where services contribute closer to 55 to 60% or more, which means China’s shift to a consumer economy will likely continue to play out for years.” In the Globe and Mail article, Ron MacIntosh, a former Canadian diplomat and now a research associate at the University of Alberta’s China Institute, notes:

“Big industrial projects will shrink in importance. That’s what happens when economies mature. Why would China be any different? The stated goal of the Chinese leadership is to move to a more consumer-oriented economy, to meet the aspirations of the rising middle class.”

And indeed, the Chinese government seems quite unperturbed by the 7.7% first-quarter GDP growth rate. The Wall Street Journal writes that officials see the data as reflecting “China's increasing emphasis on stable growth rather than the breakneck pace that has resulted in social and environmental woes and other imbalances.” And in China Daily, Wang Jun, an economist at the China Center for International Economic Exchanges, says: “The data have continued a stabilising growth trend that took shape late last year, showing that the new government does not put pursuing growth as its number-one task.”

What does slower Chinese “growth” mean for the education sector?

The aspirations of the rising middle class in China includes – high up on the priority list – a good education, and right now, that often means an education gained abroad. Writes Marguerite Dennis:

“Over 90% of Chinese parents want to send their child abroad to study in an English speaking country. In December 2012, the College Board reported that the number of Chinese taking the SAT exam increased 48% over the previous year. Chinese students studying in US colleges and universities increased 23% last year and 27% of all overseas Chinese study in the US. The UK has a 22% market share followed by Canada at 15%.”

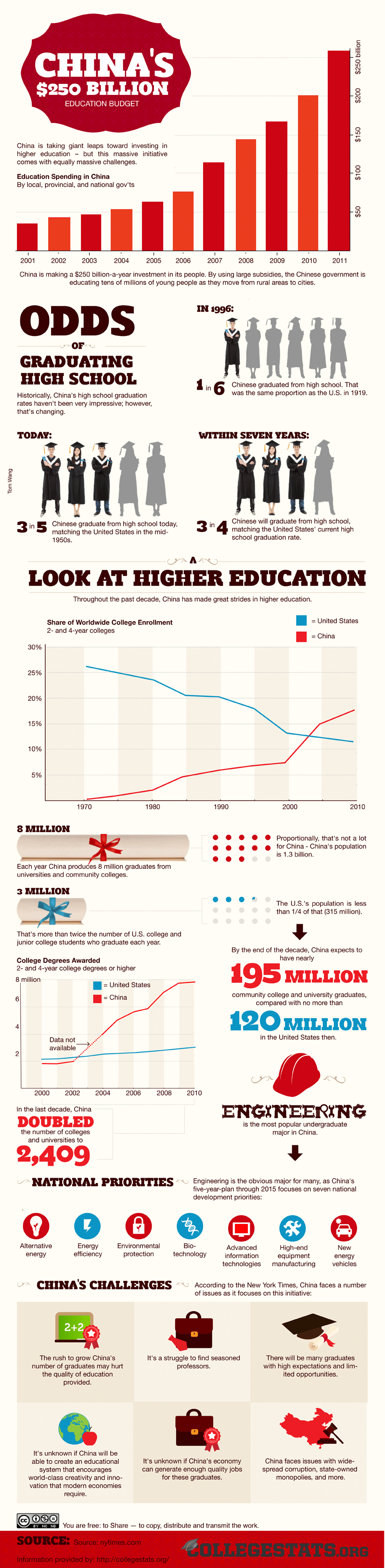

At the same time, the Chinese government is investing unprecedented sums in its domestic education system – to the tune of US $250 billion a year (see the infographic below). Education is simply one of the economic – and social – areas to which the government wants to shift the focus. Wang Huiyao, the director general of the Center for China and Globalization and a senior visiting fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, summed it up eloquently in the New York Times at the start of this year: “Among the goals is the transformation of China from a manufacturing hub to a world leader in innovation – a grand objective. One step is to increase the pool of highly skilled workers, to 180 million by 2020 from the current 114 million. Another is to ensure that by 2020, 20% of the work force has had a college education. That would be 195 million people.

"For the past 30 years, 225 million migrant workers have made China into a world manufacturing powerhouse. The same principle will apply: nearly 195 million college graduates by 2020 will certainly change China and the world.”

The infographic below from CollegeStats.org is chock full of statistics on China's education sector.

Most Recent

-

As Iran retaliates across the Middle East, schools close, students worry, and institutions reassess transnational education Read More

-

US: Student visa issuances fell by -36% in summer 2025; OPT uncertainty among factors affecting international student demand Read More

-

Canada and India deepen educational ties; India repositions as an equal player in international education Read More