Indian, Pakistani enrolments drop sharply in UK; is new promotion agency the solution?

In a recent ICEF Monitor post, we asked:

“Can the UK’s higher education sector retain its market share despite its government’s goals to reduce immigration by whatever means available?”

The answer is still up in the air.

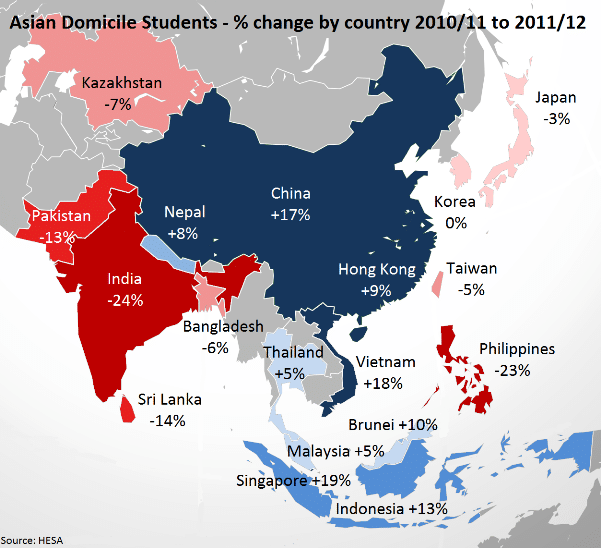

On the one hand, Britain’s overall foreign student population is slightly up, according to the Higher Education Statistics Agency – thanks especially to more Chinese students coming to study in 2011/2012 (a 16.9% increase).

But on the other, Britain has just seen its first-ever drop of international students from India (a dramatic 23.5% decline) and Pakistan (a drop of 13.4%), as well as the first-ever decline in international students coming to Britain to study at the graduate level.

An unwelcoming atmosphere?

Some are attributing the fewer Indian and Pakistani students to the tougher immigration constraints affecting international students wanting to study in Britain, which are in turn projecting a less welcoming atmosphere as a study abroad destination. Moreover, India and Pakistan are highly important markets for UK universities. Jo Beall, British Council director of education and society, commented to Times Higher Education that:

"Not only are [India and Pakistan] countries with large numbers of ambitious students aspiring to study overseas, but they are also countries with which we have historically been actively engaged in the areas of higher education and research."

In addition, despite the small overall increase in foreign students in Britain last year, there was no increase in the number of non-EU students going to Britain to study – for the first time in years.

New agency set up to promote Britain as a study destination

Perhaps partly in response to accusations that it is driving foreign students away through its visa clampdowns, the UK government just announced that it has established a new agency – Education UK – dedicated to increasing international exports. Education UK will prioritise India and the Middle East as targets. It is has been launched jointly by the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS), which oversees universities, and UK Trade and Investment (UKTI), which helps UK-based businesses with their ventures in international markets. On a recent visit to India, the UK’s Skills Minister Matthew Hancock, who also announced the formation of Education UK, explained:

“We are in a global race and other countries are presenting attractive and co-ordinated offers, so Education UK is a vital step in bringing together the UK sector to drive its international engagement, particularly on high-value opportunities.”

The new agency will reportedly focus on the following core activities:

- identifying and developing education export opportunities;

- facilitating UK consortia to respond to targeted international opportunities;

- helping to ensure effective responses to large-scale commercial opportunities.

But some worry the establishment of Education UK will not be enough to alter the perception that Britain is no longer welcoming to foreign students. Said Alex Bols, executive director of the 1994 Group, which promotes excellence and teaching within 11 small, research-intensive universities:

“We need more joined-up government. UKTI on the one hand is promoting UK education whilst at the same time, the Home Office and UK Border Agency are restricting access. The government’s ambition to limit net migration to ‘tens of thousands’ is in clear conflict with the wish to expand the UK’s share of the international student market.”

Ability to work during and after study a key factor for international students

The UK’s tough immigration policies are particularly off-putting to international students who want to work while studying or – especially – work in the UK after they finish their students. There is a striking account of one Chinese student’s experience with this in The Guardian. The student told the paper that government changes to visa rules have:

“ … seriously affected her career. When she chose to come to Britain, she had the right to work for two years post study: last year that was largely removed. ‘The money I spent hasn’t bought what I expected, no matter how hard I have tried.’”

As Britain restricts work opportunities for foreign students, other study abroad markets such as Australia and Canada are, if anything, trying to expand them. At the same time, the UK’s main competition as a study abroad destination, the US, is increasing its enrolments of international students.

Can the UK afford to risk losing international students?

The UK, like the US, is facing declines in enrolments from domestic students. But despite the rise in tuition fees, applications for 2013/14 were slightly up, and the government has relaxed restrictions on domestic recruitment, perhaps in an attempt to stave off the drop many institutions suffered in 2012/13 numbers compared with the previous year. There is much at stake. A new report from the consultancy firm London Economics (for the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills) estimates how much the UK economy stands to lose from the fall in student numbers this year; according to Times Higher Education:

“The BIS report says a reduction of 30,000 undergraduate students would cost the UK economy at least £6.6 billion over the next 40 years.”

Meanwhile, adds the report: “Higher education exports are valued at £8.8 billion, of which approximately £7.6 billion is associated with international students coming to study in the UK.” We can only watch and wait to see if the new Education UK agency can effectively promote Britain as a welcoming study abroad destination amid the stringent visa rules affecting international students there. It will have not only the visa restrictions to deal with; it will contend also with other leading markets’ growing conviction that international students are essential to their economies and relationships in the world.