China and India to produce 40% of global graduates by 2020

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has just released a new report, which is part of the Education Indicators in Focus series, looking at higher education graduates between the ages of 25 and 34 in OECD and Group of Twenty member countries - 42 countries in total. Top findings include:

- The expansion of higher education in rapidly-developing G20 nations has reduced the share of tertiary graduates from Europe, Japan and the United States in the global talent pool.

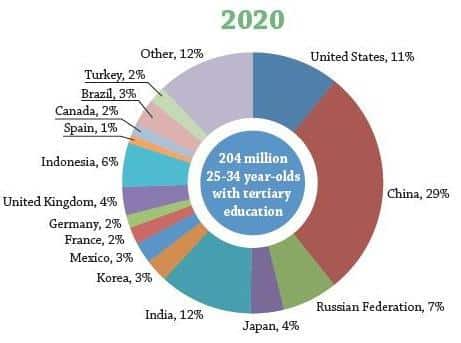

- If current trends continue, China and India will account for 40% of all young people with a tertiary education in G20 and OECD countries by the year 2020, while the United States and European Union countries will account for just over 25%.

- The strong demand for employees in “knowledge economy” fields (i.e., STEM) suggests that the global labour market can continue to absorb the increased supply of highly-educated individuals.

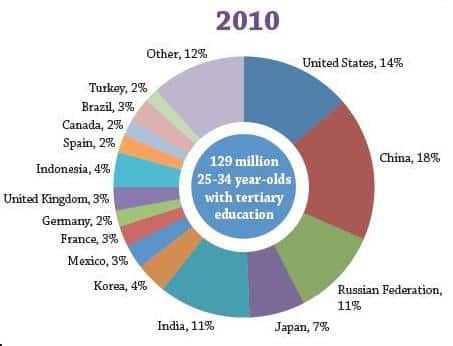

Highlights: 2010 vs. 2020

- China is expected to produce 29% of all higher education graduates aged 25-34 (up from 18% in 2010);

- the United States is expected to produce 11% of all those graduates (down from 14% in 2010);

- India, which produced 11% of graduates in 2010, is expected to overtake the United States and produce 12% of the share of graduates by the end of this decade;

- the UK’s share should increase from 3% in 2010 to 4% in 2020;

- significant declines are forecasted for Japan (from 7% to 4%) and the Russian Federation (from 11% to 7%);

- in 2020, 6% of young graduates will hail from Indonesia.

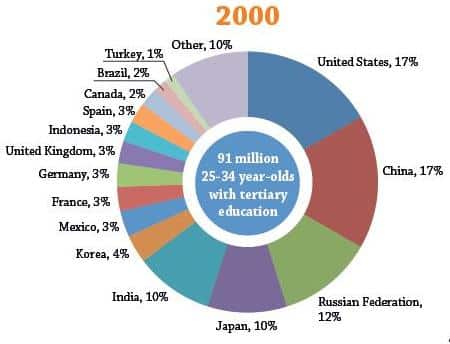

Share of 25-34 year-olds with a tertiary degree across OECD and G20 countries (2000, 2010, 2020)

The global talent pool has grown rapidly over the past decade

In 2000, there were 51 million 25-34 year-olds with higher education (tertiary) degrees in OECD countries, and 39 million in non-OECD G20 countries. Over the past decade, however, this gap has nearly closed, in large part because of the remarkable expansion of higher education in this latter group of countries. For example, in 2010 there were an estimated 66 million 25-34 year-olds with a tertiary degree in OECD countries, compared to 64 million in non-OECD G20 countries.

If this trend continues, the number of 25-34 year-olds from Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, the Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia and South Africa with a higher education degree will be almost 40% higher than the number from all OECD countries by the year 2020.

The number of higher education graduates will continue to grow

It’s likely that the global talent pool will continue to grow across most OECD and G20 countries, and that the fast-growing G20 economies will continue to account for an increasingly large share. According to OECD calculations, there will be more than 200 million 25-34 year-olds with higher education degrees across all OECD and G20 countries by the year 2020. What’s more, 40% of them will be from China and India alone. By contrast, the United States and the European Union countries are expected to account for just over a quarter of young people with tertiary degrees in OECD and G20 countries. In fact, these projections may underestimate the future growth of the global talent pool, because a number of countries are pursuing initiatives to increase tertiary attainment rates even further. For instance, in 2009 the United States established a goal to become the nation with the highest proportion of 25-34 year-old university graduates by 2020. To meet this target, officials estimate that the proportion of younger adults in the US with a tertiary degree will need to reach 60% by the end of the decade. In addition, the European Union established a goal to increase the percentage of 30-34 year-olds who have completed tertiary education by at least 40% in each EU country by 2020. In 2009, Belgium, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom already reached this goal for the larger 25-34 year-old population. Meanwhile, China – which has quintupled its number of tertiary graduates and doubled its number of tertiary institutions in the last 10 years – is also pursuing ambitious objectives.

By 2020, China aims for 20% of its citizens – or 195 million people – to have higher education degrees. If this goal is realised, China will have a population of tertiary graduates that is roughly equal in size to the entire projected population of 25-64 year-olds in the United States in 2020.

The “knowledge economy” must grow to absorb the growing talent pool

In many ways, the rapid expansion of the global talent pool – and its expected growth in the future – is no surprise. Since higher levels of education are strongly linked to higher employment rates and larger earnings premiums, individuals have strong incentives to pursue more education. Similarly, as national economies continue to shift from mass production to “knowledge economy” occupations, countries have strong incentives to build the skills of their populations through higher education. At the same time, the explosive growth of the talent pool raises an important question: 'Will the global labour market continue to absorb the increased supply of higher-educated workers in the future?' Evidence from science and technology occupations – jobs emblematic of the knowledge economy – may provide some insights.

STEM in the spotlight again

On average across OECD countries, human resources in science and technology occupations (HRST) represented more than a quarter of total employment in 2010. In Luxembourg, Sweden, Denmark, and Switzerland, HRST workers accounted for more than 40% of all employees, while in India, China, and Indonesia, they accounted for less than 10%. More importantly, between 1998 and 2008, employment in HRST occupations increased at a faster rate than total employment in all OECD and G20 countries with available data. The average annual growth rate was uniformly positive, ranging from 0.3% in China to 5.9% in Iceland. This consistently upward trend – and even the comparatively smaller shares of HRST occupations in fast-growing economies like China – signals that the demand for employees in this knowledge economy sector has not reached its ceiling.

Conclusions

Applied to the overall labour market, these findings suggest that individuals from increasingly better-educated populations will continue to have good employment outcomes, as long as economies continue to become more knowledge-based. These findings also suggest that countries would be well-advised to pursue efforts to build their knowledge economies, in order to avoid skills mismatches and lower private and public returns on education among their higher-educated populations in the future. The global talent pool has never been larger – and will continue to expand, with rapidly-growing G20 nations likely leading the way. Source: OECD

Most Recent

-

British Council says student recruitment to UK higher education will get a boost this year from South Asia and the “Trump effect” Read More

-

New Zealand expands post-study work opportunities for international students Read More

-

As Iran retaliates across the Middle East, schools close, students worry, and institutions reassess transnational education Read More