Taiwan’s higher education enrolment starts a downward slide

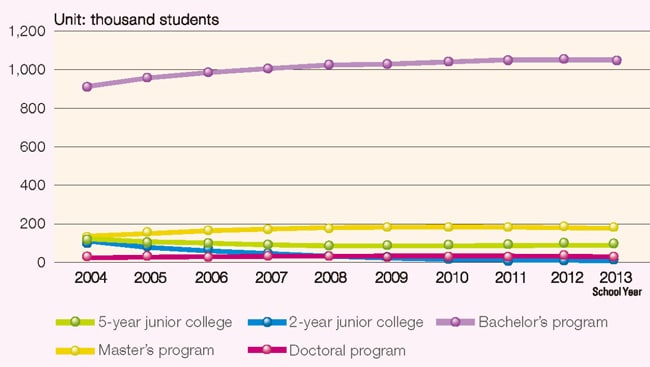

A predicted downturn in higher education enrolment in Taiwan has started to kick in more strongly over the last year. Earlier this month, the country’s College Entrance Examination Enrollment Distribution Committee released figures indicating that as many as 23 Taiwanese universities will face enrolment shortfalls this year. All told, 203 academic departments will admit fewer students than expected, and the drop will be particularly acute for six private institutions. Mingdao University, Huafan University, Hsuan Chuang University, the University of Kang Ning, Kainan University, and Chung Hua University will all see student commencements of less than half of their admissions targets for the year. "Although some of these schools had similarly low enrolment numbers between 2008 and 2010, this year’s overall situation is historically the worst faced by the schools to date," an unnamed committee member said to the Taipei Times. Echoing the experience of some of its East Asian neighbours (Japan and Korea, in particular), Taiwan’s declining birth rate is a big part of this story. After years of low birth rates, the Ministry of Education projects that university enrolment in Taiwan will fall by about a third through the next decade. Ministry forecasts had projected a sharp decline in Taiwan’s population of university students beginning in 2016, and indicate the country’s university enrolment could decline by as many as 310,000 students overall (that is, in both private and public universities) from 2013 to 2023. Those projections are now being reinforced by current-year data, such as the enrolment figures from the Enrollment Distribution Committee, and also by updated government forecasts. Lee Yen-yi, Director General of the Higher Education Department at the Ministry of Education, recently explained to Taiwan Business Topics that new student enrolment for 2015/16 dropped to 250,000 students, from 270,000 the year before, for a year-over-year decline of 7.4%. "Going forward, this trend will become increasingly pronounced and steep," Mr Lee added. "By the 2019 academic year, new enrolment will drop by 30,000 students from the previous year. Student numbers are dropping, but the schools are still there. The number of students they’re competing for is dwindling." But a lower birth rate is only part of the equation at work in Taiwanese higher education as the system itself has expanded considerably over the past two-to-three decades. In the mid-1980s, there were less than 30 universities in Taiwan, and under 200,000 students enrolled in higher education (for a gross enrolment ratio of about 21%). Again from Taiwan Business Topics: "Fast forward 20 years to 2005 and a vastly different educational landscape comes into view, with 145 colleges and universities serving 1.1 million students - and 82% of 18- to 21-year-olds enrolled." Simply put, Taiwan now has more universities than it needs. Last year, the Ministry has announced plans to merge or close up to 52 institutions, and the first such moves are already underway. Some institutions are forming consortia to combine faculty and resources, including shared or joint programmes. And two public institutions in the northern city of Hsinchu have filed a formal proposal with the ministry to merge. Under the plan, which is meant to be implemented gradually over the coming decade, National Tsing Hua University will effectively absorb the National Hsinchu University of Education.

Aligning with the job market

Aside from this supply-demand disconnect in Taiwanese higher education, there is also the question of graduate outcomes. As a recent Brookings Institution report puts it, "Each year, approximately 300,000 students graduate from universities, among which many become unemployed."