The agent question: New data has the answer

In international education circles, the use of education agents is simultaneously controversial, and widespread. But, as a new report published today by The Observatory on Borderless Higher Education (OBHE), The agent question: insights from students, universities and agents, notes, the debate has been flawed so far by “dependence on anecdote over data.” Everyone has an opinion, but based on what? Personal experience and/or preconceived notions do not, on their own, speak of overall trends or practices in a global marketplace. The report draws on three streams of data in an effort to “make the agent debate less rhetorical and more evidence-based,” and concerns itself with answering three main groups of questions:

- “Scale and Scope: how many agents, playing which roles, located where? How many and which kinds of students and institutions use agents?

- Evaluation: how do students and institutions rate the services provided by agents? How do agents regard institutions?

- Legitimacy: should the education agent, or certain types or services of agents, be welcomed or shunned? Are certain agent relationships inherently problematic? Can regulation sort out the ‘good’ from the ‘bad’?”

To answer these questions, the OBHE compiled data from students, institutions, and agents themselves. For agents, they drew on Agent Barometer data, the i-graduate/ICEF-founded survey of education agents around the world. For students, they turned to the i-graduate’s International Student Barometer (ISB), the world’s largest survey of international student satisfaction, which includes a section on students’ use of, and satisfaction with, agents. For institutions, OBHE undertook a survey of institutional use of agents across seven countries.

Systems in place to identify the best agents

Across the world, there is no one common agent regulation system, but The agent question outlines the main ways the major destination markets of the US, Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand provide agent training as well as established processes for qualifying agents. After providing details on each market, the report provides this general assessment:

“Regulation of education agents is diverse … and very much evolving. The well-established voluntary arrangements in Australia and New Zealand steer prospective students and institutions to a list of ‘registered’ agents. The British Council’s regime plays a similar role. Canada’s immigration-focused system will similarly distinguish agents ‘serious’ about Canada, and certainly offers very practical advantage to agents themselves in terms of the ability of offer visa advice within the law."

The report notes that limitations so far to the overall regulatory environment include distinct national and international regulation systems as well as few regulatory systems in the sending countries out of which local agents operate. It suggests:

“More robust local regulation, in the countries where agents are based, may also permit greater partnership between host and destination countries.”

Taking the agent pulse

To report on the size, services, and performance of agents across the world, The agent question looked at 2013 data from the i-graduate/ICEF Agent Barometer, which surveys agents working with institutions in secondary and higher education, and also language and vocational schools. The sample used by OBHE included 1,194 agent responses across 117 countries. As much as the sample is analysed according to nationality, there is one notable limitation. Despite China being the largest market for international students and the heavy use of agents among Chinese students, agents located in China represented only 2.5% of the 2013 sample. The report notes, “The China-based agents in the sample were larger than average in terms of staff and placement volume, countering but far from eradicating under-representation.” Here are some of the highlights from this section of the report:

- Agents placed most international students (50%) in language courses, with about 35% going to higher education (split quite evenly between undergraduate and graduate courses). Distance education currently accounts for a relatively small proportion of placements – about 15%.

- Nearly three-quarters of surveyed agents (72%) work in small organisations of 2-10 counsellors; 23% work in teams of 10 or more counsellors.

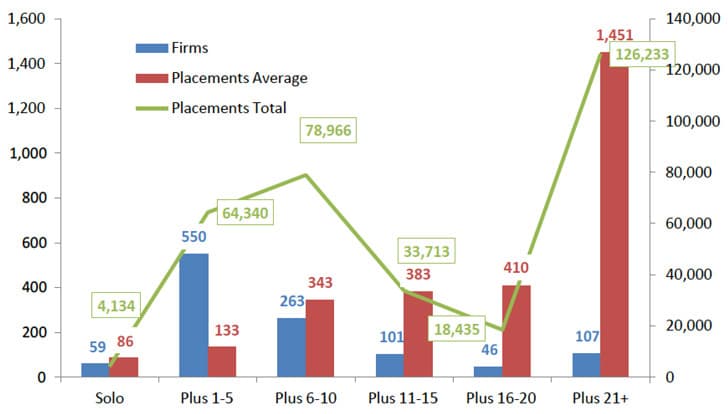

- Bigger agencies, more students: firms composed of five or fewer counsellors accounted for just over half of the sample but were responsible for only 21% of placements, while firms with 20+ counsellors (composing only 10% of the sample) facilitated almost 40% of placements.

- Most agencies work with a large number of institutions, and this trend intensifies among the largest agencies. 20% work with fewer than 10 institutions, suggesting more of a niche focus and/or smaller size for those counselling centres.

- Specialisation is alive and well. For example, “about 57% has a primary focus on language school placement, and 55% has a primary focus on public higher education, but only 22% has a primary interest in both sectors.” Agents also tend to specialise within a sector (e.g., private vs. public institutions).

- Data analysis suggests universities and colleges benefit when they work with agents with relatively few institutional relationships; however, few agents work this way, seeing “multiple relationships as the only way to achieve growth or even sustainability.” The report sums up the situation this way:

“The current situation might be judged a healthy compromise between agents and higher education institutions. To hit recruitment targets, institutions typically desire geographical breadth and operational sophistication of agents, both of which require or favour scale. But an agent may need multiple clients in order to support that scale. Institutions trade single agent performance for breadth and skill of operation, and rely on multiple agent relationships; while agents give up close fit with a few clients for a workable fit with many.”

- About two-thirds of the sample had taken steps to acquire formal agent accreditation such as the ICEF Trained Agent Counsellors (ITACs) or the British Council’s agent certificates. But a significant portion – one-third – had not. The report explains: “In a situation where all certifications are voluntary and most agents place students in many countries, the cost of compliance across multiple regimes is high and the penalties for non-compliance low and often vague.”

What do institutions say?

In late 2012, The OBHE surveyed 181 higher education institutions in seven countries: Australia (14), Canada (37), Malaysia (7), Netherlands (7), New Zealand (10), the UK (52), and the US (54). Most were degree-granting universities and colleges. Highlights include:

- The vast majority of respondents reported use of education agents.

- The majority of agent relationships reported were primarily in Asian markets (Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Thailand, Vietnam), as well as Brazil, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

- Across the sample, the number of agents used is highest in China.

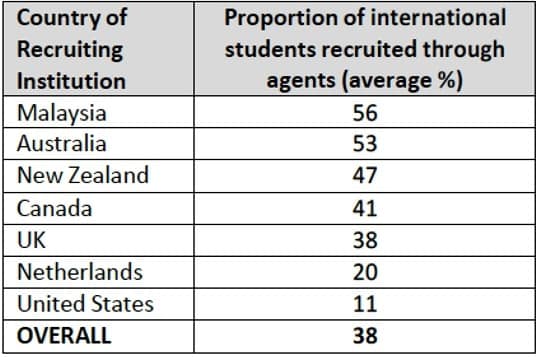

- Regarding the proportion of international students recruited via agents, there were huge variations but the average was about 33% across all markets, and 38% in the top seven destination markets.

- Overall, institutions reported satisfaction with their agent relationships. Reasons included “great market coverage,” delivery of ”better-prepared and counselled students,” local knowledge and cultural sensitivity, and help promoting institutional brands.

- Negative views included sentiments such as agents take “maximum share with minimum risk,” entail more administrative work, individually produce low volume of business, and generate lower-than-expected conversion rates, are not consistently good across markets, and don’t meet contracted targets.

- The countries with the longest histories of working with agents – Australia and New Zealand – rely the most on agents as a recruitment method.

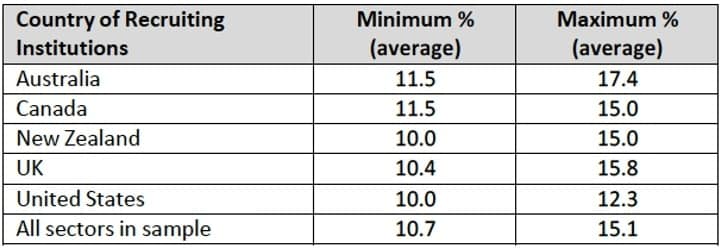

- Commissions are the most common form of agent payment, ranging from a minimum of 10% to 17.4% of first-year tuition fees.

- Formal agent contracts are common across all seven countries, and in six of the seven countries, the majority of surveyed institutions use performance management and reviews to determine whether contracts will be renewed. But in the US, only a quarter of the institutions reported this practice, “an indication that such relationships are less developed and formalised” in America.

Adding the students’ perspective

The i-graduate International Student Barometer (ISB) is the world’s largest survey of international student satisfaction. It asks first-year students whether they used an education agent before enrolling and gathers feedback on the experience of those who did. The OBHE examined “mainly a subset of ISB data covering 48 comprehensive universities in Australia, the UK and the United States, representing about 27,000 first-year international students.” Here are the highlights:

- Roughly a third (32%) of the students in the sample had used an education agent, up from about 10% five years ago.

- The youngest students – for example those seeking admission to undergraduate programmes – are much more likely than more mature students (e.g., seeking entry to doctoral studies) to use agents.

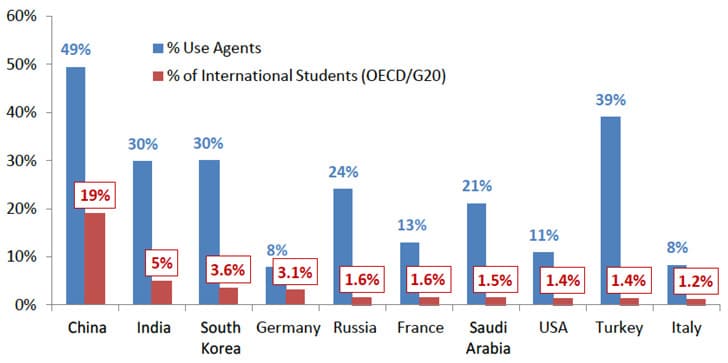

- Students in key Asian markets are among the most likely to use agents.

- International students in Australian schools are much more likely to have used an agent (50%) than those in British or American ones (27%). “The higher Australia ratio is consistent with near-universal use of agents among the nation’s universities, and Australia’s longer-established and more active regulation of agents,” notes the report.

- Agent certification or an institution’s recommendation of an agent are relatively insignificant ways students find agents. The ability of agents to market themselves and make their services known to students seems to be their best method to attract business.

- Surveyed students now consider agents almost as influential as institutional websites when they look back on how they made their enrolment decisions (32% vs. 37%, respectively - a very different situation than in 2007, where agents were considered influential by only 12%, versus websites’ 44%.

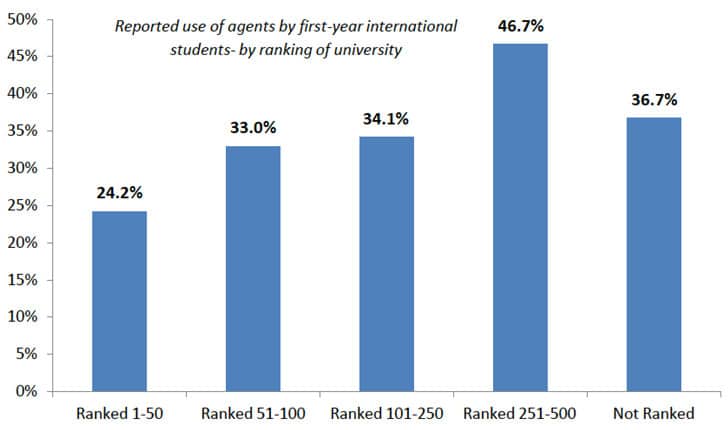

- Agent use is more common among students who enroll at the lower-ranked universities than at the most prestigious ones, a finding the report suggests may be due to the more complex and risky process of assessing lesser-known choices.

- There is wide variation in how much students pay the agents they use, from nothing (25%) to more than US$5,000 (13%), with an average estimated at US$500.

- A large majority of all students who used agents report being “satisfied,” regardless of fee level (and some of this group are “very satisfied”). “In fact, even among students paying an agent in excess of US$5,000, 75% are satisfied or better.”

What the findings suggest

The agent questionconcludes by rejecting any notion that there is an intrinsic problem with the practice of using agents – and it does so on the basis of the data analysed for the report. It acknowledges that bad practice among agents certainly exists, as it does among actors in any industry. But on the whole:

“There is simply no evidence of widespread dissatisfaction on the part of students or institutions with respect to agent use. Indeed, student overall satisfaction with agents is similar to student satisfaction with institutions.”

The report goes on to back up that contention with more data. While we have space to report only the summary findings here, we encourage you to visit the i-graduate website to request an abstract or purchase the complete report. For now, we will leave off with its final paragraph regarding thoughts about the healthy maturation of an industry in which agent use continues to grow:

“If done well, evolving regulation, in host and destination countries, will help accentuate the benefits of agents and minimise scope for bad practice. The industry needs to step fully into the light. As the industry adage goes, sunshine is the best disinfectant. Industry consolidation will also play a positive role. Just as important, data on agent use, performance, and views… is essential in transforming the agent debate from rhetorical to evidence-based. The task at hand is not to blindly endorse or reject agents but to acknowledge the validity of the role; and for those students, institutions and governments who choose to engage with agents, to continue to seek ways to optimise the legitimate benefits for all concerned.”