Cloudy outlook for 2+2 programmes in China

Collaboration on joint programmes seems to be a great win-win solution for students, academic institutions, and the receiving and sending countries. The Chinese government has encouraged such collaboration in the past but more recently has increased its scrutiny and the rigour of its approval processes for joint programmes. We hear a broad-based consensus that it has become very difficult to get approval for such programmes for all but the most prestigious Western and Chinese universities. In this article, we analyse the available statistical information on these joint initiatives. Let me quote directly from the relevant Chinese regulations:

“The State encourages Chinese-foreign cooperation in running schools to which high-quality foreign educational resources are introduced… The State encourages Chinese-foreign cooperation in running schools in the field of higher education and vocational education, and encourages Chinese institutions of higher learning to cooperate with renowned foreign institutions of higher learning in running schools.”

We want to clarify that the international joint programmes mentioned in this article are only at the undergraduate level in China. International joint programmes can be created in various ways:

- so-called “2+2 programmes” (two years of study in China followed by two further years overseas);

- three years in China +1 overseas;

- one year in China +2 overseas +1 in China;

- two years in China +1 overseas +1 in China.

The bottom line is that the Chinese students must study in China for at least two years over the course of the joint programme. Such programmes are different from an international transfer arrangement, which typically means that a qualified student can transfer to a foreign university/college after successfully completing his/her first year of undergraduate studies at a Chinese university. Students enrolled in international joint programmes should be granted two bachelor’s degrees – one from the Chinese university and the other from the foreign university/college – upon graduation. During the study abroad period, the students are still considered registered students of the Chinese university. In contrast to this, students participating in international transfer programmes are no longer registered students of the Chinese university after transferring, and will only receive a degree from the foreign university/college at graduation. We see a number of strategic and academic advantages of such joint programmes:

- Potential alignment of the curriculum;

- Knowledge transfer between the involved entities;

- Increased appeal and value of the academic programme;

- Increased revenue through minimal international marketing efforts;

- Predictable and stable incoming students yearly;

- A productive partnership that may bring more collaboration opportunities as well as convenience for certain international activities (e.g. improved logistics);

- The Chinese partner(s), considered as the equivalent(s) of your institution in China, may be a strong reference for the overall branding and marketing in China, which could overcome the difficulties or misunderstandings caused by ranking, in some cases.

We note as well a number of significant disadvantages that could be associated with 2+2s and their variants:

- The level of effort required to establish the programme (e.g. course credits, credentials, and curriculums);

- Similarly, the ongoing effort required to support the collaboration over time;

- As Chinese students from the international joint programme are allowed to study overseas for no more than two years in most cases, the tuition revenue is lower than it is from fully matriculated students.

Let’s also be frank about the advantages for both partners in respect to overall enrolment management, tuition generation, and international student recruitment: both partners generate tuition revenue. The Chinese entity is able to raise tuition on domestic students and the US, or more generally international programmes, can attract a regular flow of Chinese students with a predicable academic standard without the competitive recruiting effort.

History of dual degree programmes

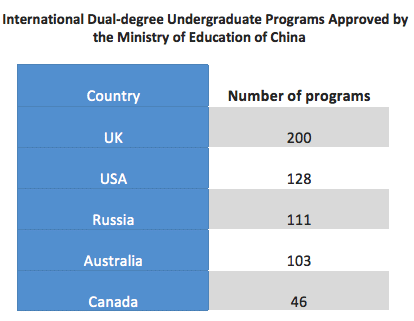

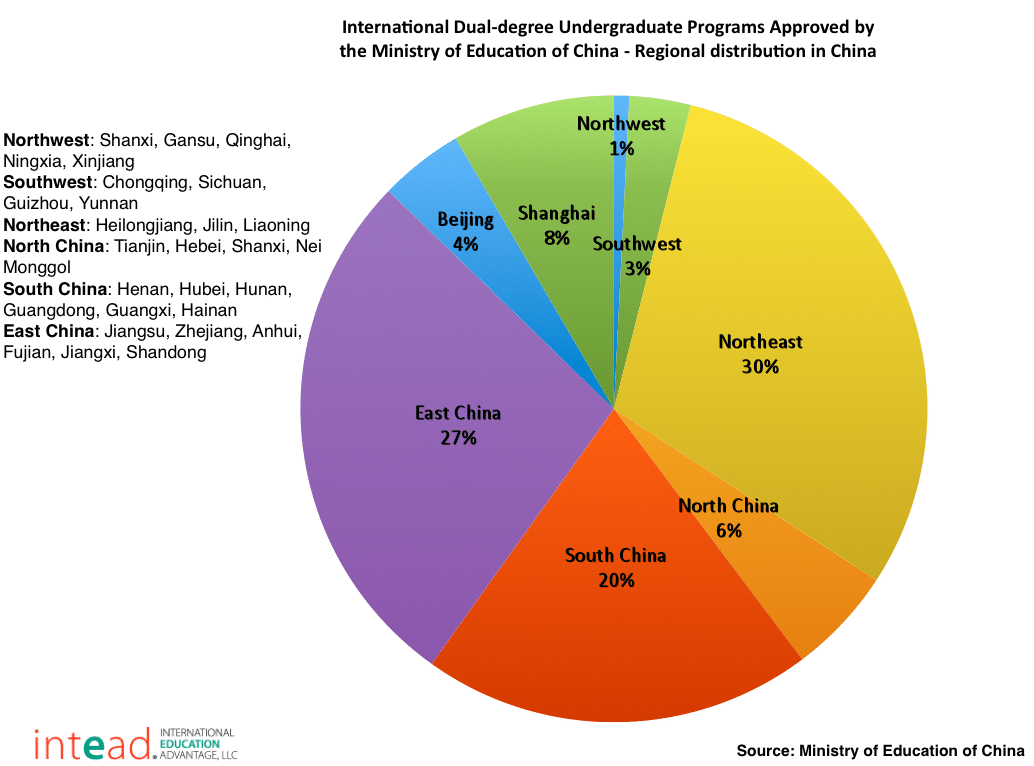

Our understanding is that the development of international joint programmes in China has undergone two basic stages. The earlier stage was guided by a set of tentative rules, by which any Chinese university in practice was able to collaborate with an unrestricted number of indefinite foreign higher education institutions to establish unspecified programmes. As a result, some Chinese universities became proactive in their approach to these loose regulations and effortlessly optimised their relationships with foreign partners by building up as many international joint programmes as they possibly could. For instance, Harbin Normal University (HNU) from the Heilongjiang province built all of its 19 existing international joint programmes with six Russian, two British, two Australian, one American, and one South African university over that period. In the latter stage of development, more restrictions were applied to the administrative approval of international joint programmes. It became more and more challenging for Chinese universities to create international joint programmes with foreign partners that did not have a recognisable academic performance in their own countries. In addition, programmes in certain academic fields, such as applied technologies and engineering, were preferred by the authority in the approval process. In practice, most Chinese universities were allowed to establish only one new joint programme.

International geographic distribution

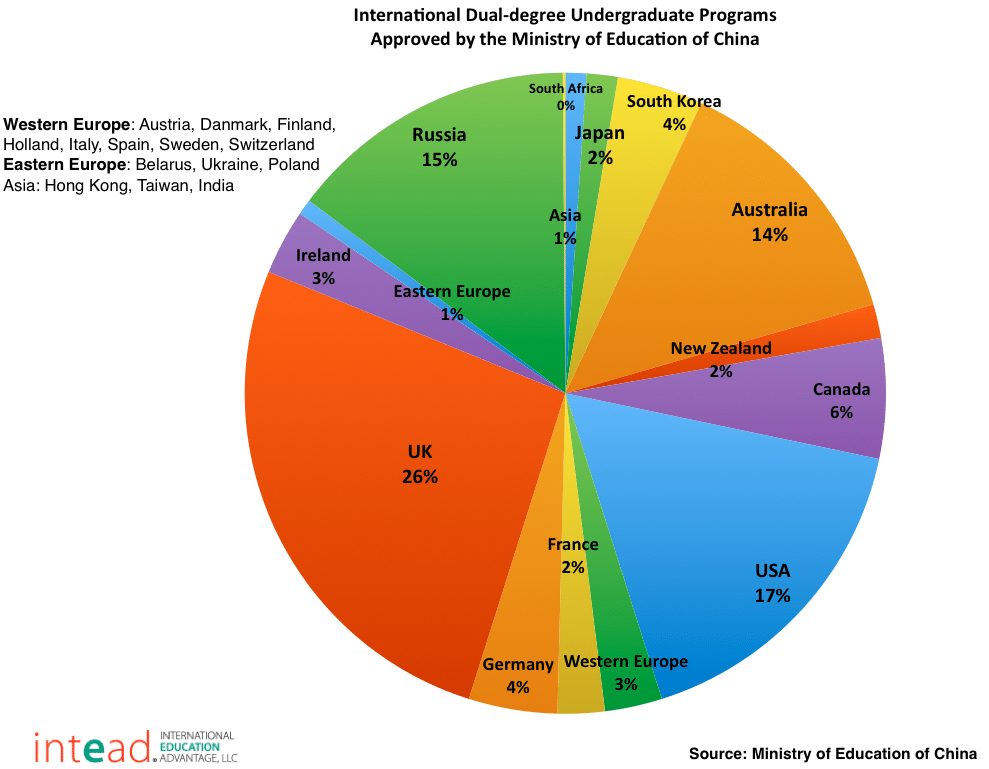

Let’s look at the overall distribution of the destination countries for the 760 programmes approved by the Chinese Ministry of Education. The following figure summarises the worldwide distribution by countries if they account for a sufficient number of programmes or region.

Conclusion

As we all know, international enrolment of Chinese students has increased significantly over the past few years. Direct enrolment has driven this process, though we have not seen any reliable information on the breakout of enrolment figures. The market forces for direct enrolment are strong. Western universities are interested in maximising tuition revenue. Admissions departments in Western universities are tasked and organised to recruit full-time, degree seeking students. In particular in China, the commercial agent and counselling services drive direct student enrolment with or without direct collaboration with universities more than any other form of academic placement.

At the same time, our subjective anecdotal impression is that the Chinese government and academic institutions have received less benefit from such arrangements than they had hoped and the honeymoon period has ended.

In Western universities, joint programmes require strong academic sponsors and they have limited motivation to sustain the extra work over the long term. Admissions departments have to own the enrolment effort even if it does not fit neatly into their standard operating processes. Our thought is that joint degrees are a valuable contributor to educational mobility and globalisation. But as a professional education marketer and strategic consultant, we see a cloudy regulatory, institutional, and market environment inhibiting the continued growth and success of these programmes. For a broader view of channels and strategies for international recruitment, please see our list of 88 ways to recruit international students.